The Small Block Chevrolet V8s

265 - 267 - 283 - 302 - 307 - 327 - 350 - 400

This page covers only unusual or exotic small block Chevy bits.

Small Block Engines

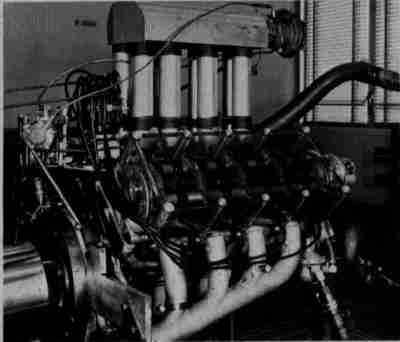

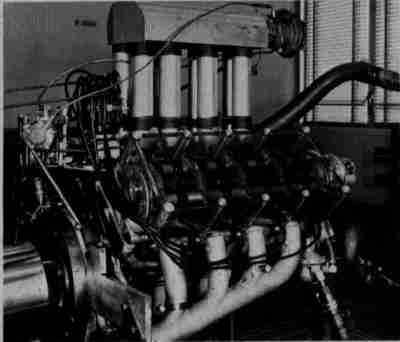

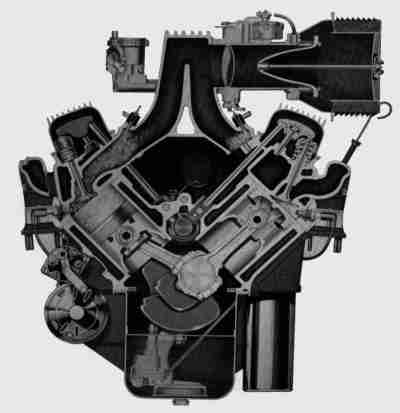

This single overhead camshaft 327 was built sometime before 1969. It had

hemispherical combustion chambers and GM-made timed fuel injection.

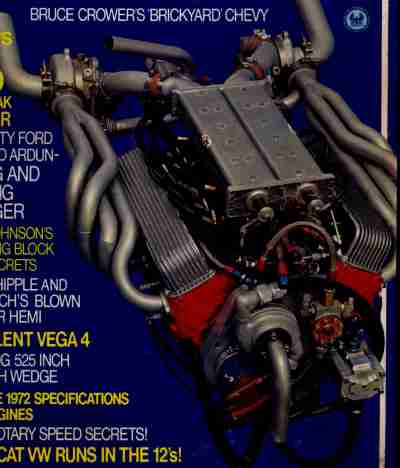

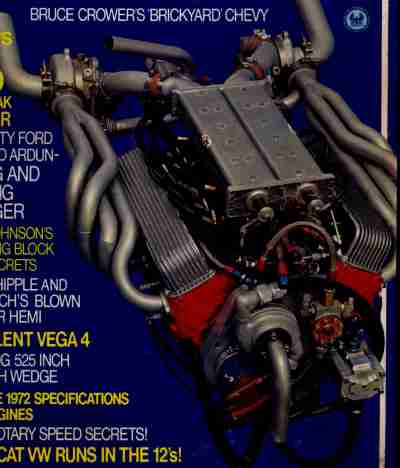

Bruce Crower's 1972 Indy stock-block. 850 HP from 203 cubic inches, with a 4-

bolt 350 block sleeved down to 3.75" and a 2.3" stroke Moldex steel crank.

Heads were ordinary 461 castings with 1.94/1.50 valves.

Want something different? How about one of Ryan Falconer's aluminum V12s?

Weighing in at just 523 pounds, they're based on small block Chevy parts.

Falconer still sells them, mostly to boat racers. You can get them in sizes

from 300 to 641 cubic inches. Cost? Bring a Styrofoam cooler full of

money...

Chevrolet, for no reason I could figure, actually built a prototype C4

Corvette with one of these. It's in the museum in Bowling Green. They

stretched the chassis about six inches, it looks like, and extended the hood

by the same amount. If it's not on display it's probably in the back; they

rotate the cars from the back to the front from time to time.

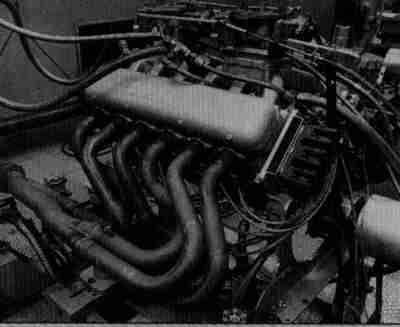

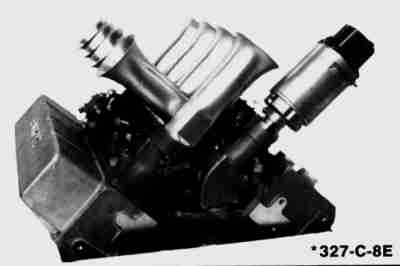

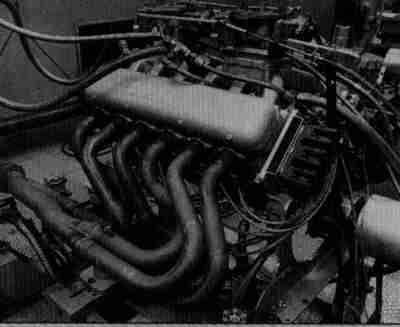

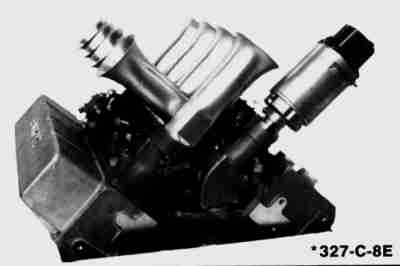

This is Bruce Crower and his 1970 Indy stock-block. It was sleeved down to

the 203-inch limit and ran 22 pounds of boost for 720HP. Does the intake

setup look a little unusual? Bruce didn't like the way the intake ports were

laid out in the Chevy heads, so he bored holes through on the exhaust sides,

welded in thickwall pipe, and made his own intake ports.

Small Block Specifications

chaos.lrk.ar.us!dave.williams (Dave Williams)

hotrod 19 Jan 93

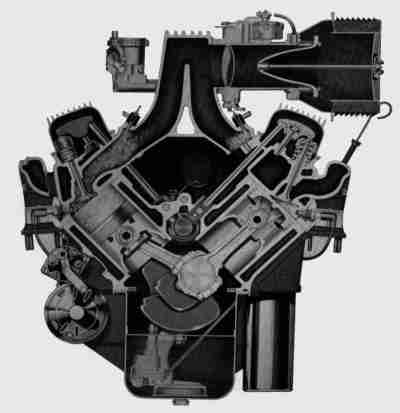

While flipping through an ancient Chilton's manual the other day I

noticed a cutaway drawing of the small block Chevy go by. A couple of

pages later something struck me as "off" about it, so I flipped back and

looked again. Turned out it was a '49 Cadillac V8, not a Chevy.

The basic layout is very close. The familiar low-slung camshaft,

paired intake ports, rear mounted distributor, etc. There are obvious

differences, of course - air gap style intake with separate valley

cover, head water comes through a separate manifold in front instead of

the intake, shaft mounted rockers instead of stud, deeper water jackets,

and (probably most important) the Caddy oiled the mains from the lifter

galleries instead of the Chevy's third "spine" oil gallery.

Now, after all that, it might not *sound* like the engines are much

alike, but in the cutaway it's pretty obvious. So I turned to an

article called "Number One" in an ancient Hot Rod yearbook, and found

the following corraborative evidence:

"...spring of '52 when Ed Cole was named chief engineer at Chevrolet...

In 1946, when Cole was chief engineer at Cadillac, where he and Harry

Barr were the driving forces behind the design of the 1949 Cadillac V8.

Barr transferred to Chevrolet in '52, at Cole's request, as assistant

chief engineer to help with the design of the new V8."

It turns out Chevrolet had had their own 230-inch V8 underway, but Cole

scrapped it for an improved version of the Caddy. The article further

mentions how the Chevy team trimmed the water jackets, combined the

intake, valley cover, and return water manifold, etc. So the Chevy

wasn't quite as revolutionary as later propaganda made out. Its parent,

the Cadillac V8, was a fairly stout device in its own right, the piece

de resistance of many engine swaps, such as the near-production-line

Fordillac and Studillac. In racing trim, the Cadillac was successfully

run at Le Mans.

For a bit of name dropping, the development crew was:

Ed Cole, Chief Engineer, Chevrolet. In charge of the Chevy V8 project.

Later became president of GM.

Harry Barr, Assistant Chief Engineer, Chevrolet. Barr did the actual

design work, porting the Caddy over in improved form.

Al Kolbe, Chief Designer, Chevrolet. Moved up from drafting room

supervisor to do the drawings and detail design of the V8.

Don McPherson, drafting room supervisor, Chevrolet. Also wore the

hat of head of the cylinder head design group. Later became

general manager of Buick. McPherson was responsible for the

5-bolt head pattern, port layout, and combustion chamber shape.

Lesser figures:

Loren Papenguth, project engineer, Chevrolet. Designed the

through-the-pushrod oiling system used by the 265.

Clayton B. Leach, motor development engineer, Pontiac: Developed the

stamped steel rocker and ball-stud layout at home in his

basement, managed to sell the idea of Cole at Chevrolet.

Later became assistant chief engineer of Pontiac.

They received approval for the new engine in early '52, and had it

designed, debugged, and in production in late '54 for the '55 model

year. GM now claims it takes them five to eight years to get a new

engine in production.

Looks like Barr, Kolbe, and McPherson are the ones primarily

responsible for the small block Chevrolet.

I'd read the article once before, of course, but it was long ago, and

wouldn't have meant much if that cutaway of the Cad V8 hadn't caught my

eye.

Small Block Heads

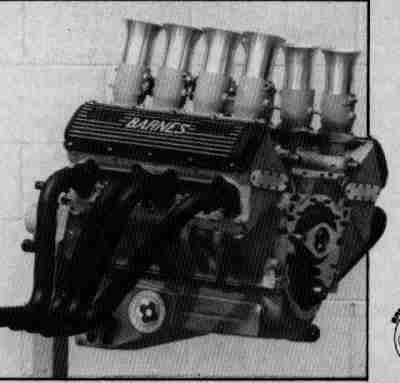

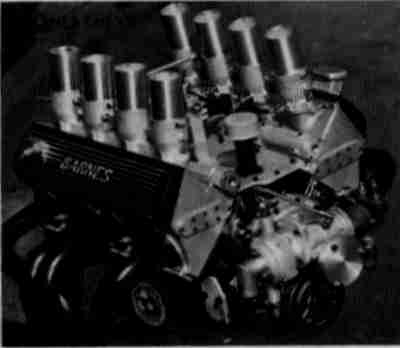

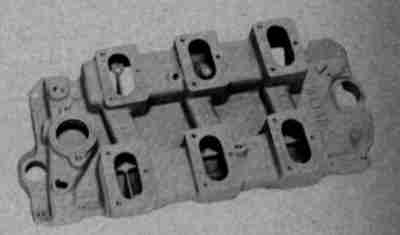

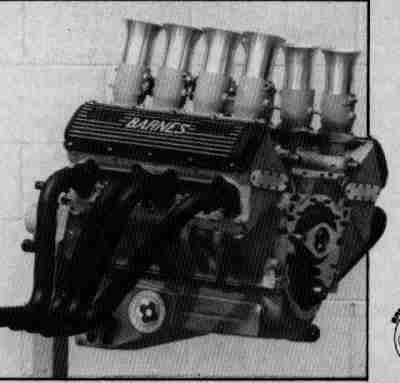

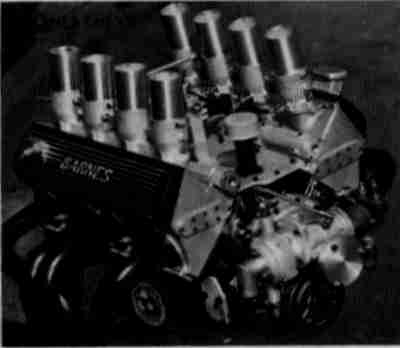

Barnes Systems made these very trick aluminum heads in the '80s. They were

intended for racing use, but weren't allowed by most sanctioning bodies.

The Barnes heads were two valve, 2.09/1.62, with the intake ports splayed

similar to the factory big block heads. 47cc wedge chambers, D-shaped exhaust

ports, special shaft-mounted needle roller rockers, and weighed 28 pounds

each.

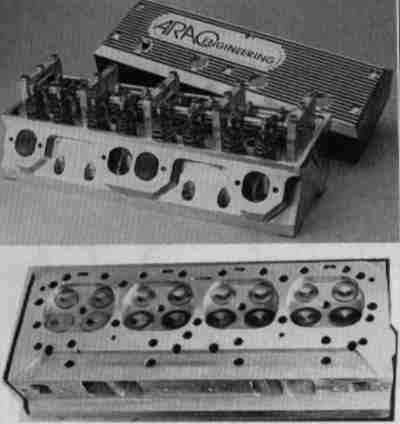

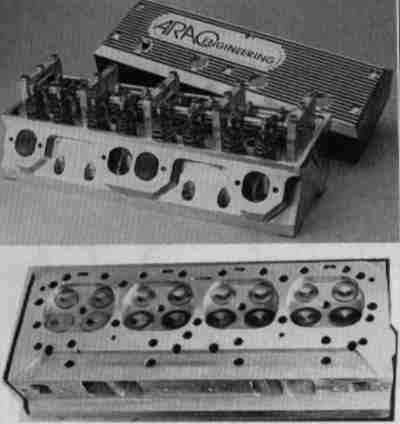

These Arao four valve pushrod heads came out in the early '90s. This pair is

for a big block, but small block heads were available too. The Araos used

stock pushrods, cams, and lifters as well as stock intake manifolds.

Small Block Valvetrain

Rev kits go in and out of style. Their original purpose was to make

absolutely sure roller lifters stayed in contact with the camshaft. Floating

a valve with a roller cam usually means knocking the roller off the end of the

lifter, with subsequent consequences.

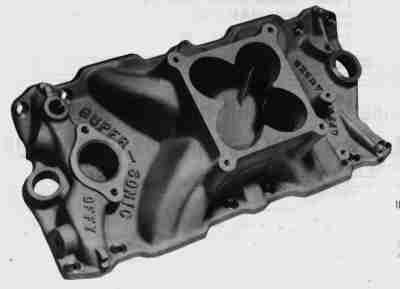

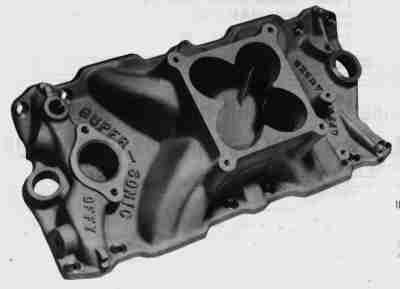

Small Block Intakes

Ever wonder why the other guys at the Saturday night feature run so much

faster than you? This cast iron dual plane racing intake is available through

Midwest Motorsport; it is externally identical to a stock Chevy manifold.

Rumor has it one of the major head suppliers is providing "reproduction" cast

iron Chevy cylinder heads, externally identical to stock, but with the latest

port and combustion chamber designs. It was bound to happen sooner or later..

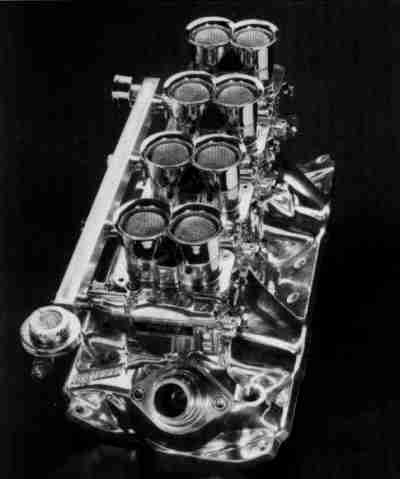

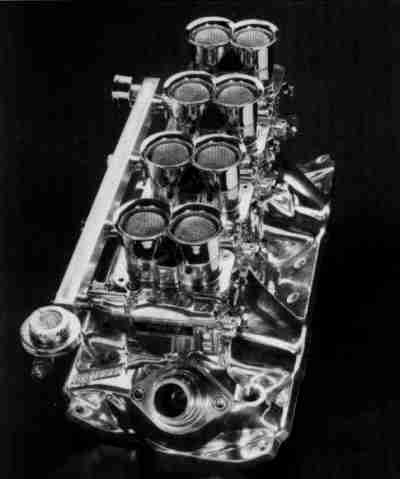

Moon cross-ram intake with DCOE Webers. Dean Moon put this engine

together for an Iso Grifo back in 1973; it's dressed for the dyno here.

This setup was popular with road racers in the 1960s.

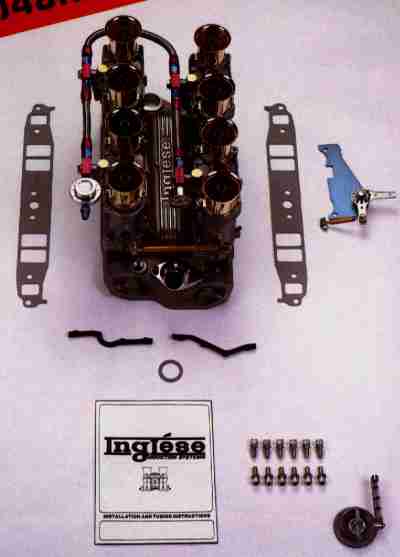

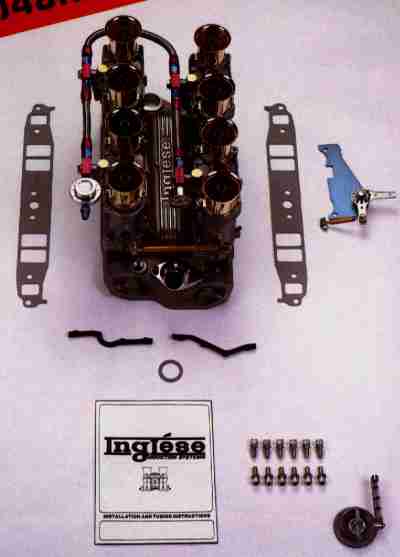

Inglese intake set up for Weber DCNF-style carbs. It came with a special

distributor drive to clear the rear carb.

Inglese intake set up for Weber IDA-style carbs. This is the most common type

of Weber intake for the Chevy.

Same IDA-type intake with IDA-pattern fuel injection throttle bodies. This

shot shows the severe angularity required to join the closely spaced ports to

the widely spaced throttles of the IDAs. The DCNFs or the side draft DCOEs

have a much smoother flow path, but the kink doesn't really seem to be a

problem; at least many successful racing cars have used this type of manifold.

The sharp pressure pulses of the independent-runner system may have something

to do with it.

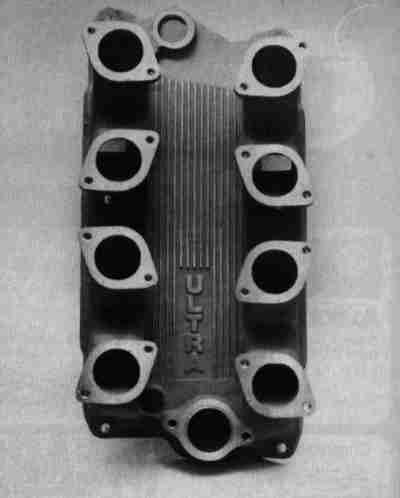

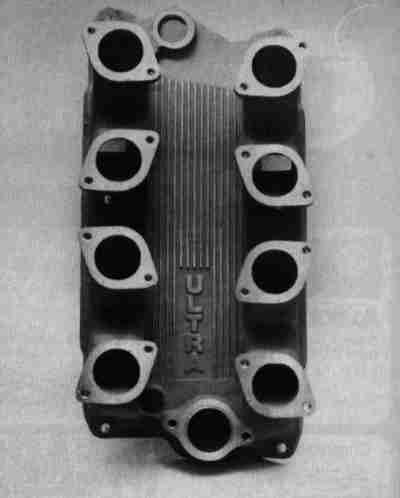

Ultra 4xIDA intake from Australia. It was AU$650 in 1982.

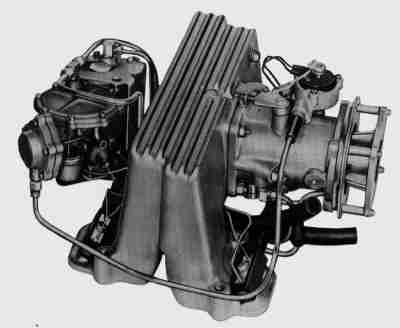

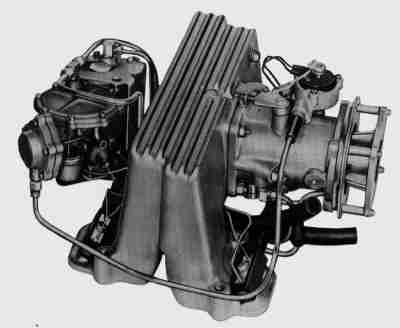

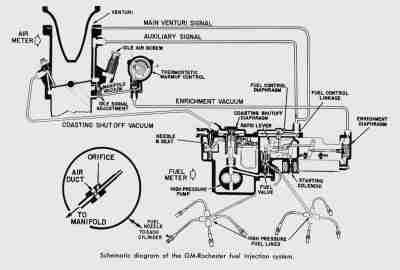

This is the famous Rochester fuel injection that was optional on the '57

Chevy. Rochester tweaked the design some every year, but nothing major was

changed.

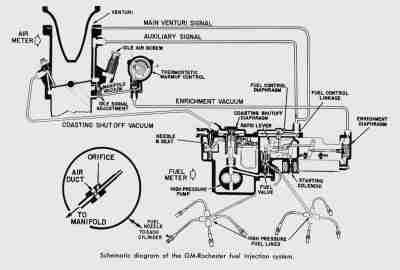

The Rochester injection used a air velocity sensor and continuous port fuel

injection. GM dropped the system because it made no more power than the much

cheaper dual quad carburetor setup and the high cost kept sales down.

The Rochester injection was not a dead end; the wildly-successful Bosch K-

Jetronic mechanical injection was based on technology licensed from

Rochester's patents. Bosch simplified the system, invested in the tooling to

make it profitably, and went after a higher-end market than Rochester had been

trying to sell to. VW Beetles used Bosch D-Jetronic electronic fuel

injection; Porsches, Ferraris, and Loti used K-Jetronic mechanical fuel

injection.

If you look closely you can see the air lever, spill valve, and electric cold

start valve, which were carried over in modified form by Bosch. Bosch deleted

the coasting fuel shutoff and simplified the venturi/ratio lever/enrichment

diaphragm setup into a simple air paddle operating the spill valve directly.

It wasn't as simple as it looked; Bosch spent many, many hours of design and

dyno time to make it work as intended.

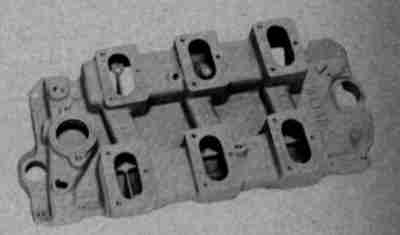

Weiand dual plane 4x2bbl intake, circa 1961. All four carbs operated at the

same time. With proper tuning good gas mileage could be obtained.

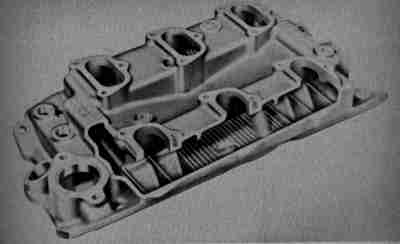

This is a log-type manifold from Weiand. Log manifolds were popular in the

1940s and 1950s when carburetors were very small. This manifold has two

barrels over each port pair, plus two center carbs. If the carbs were staged

it would have been quite streetable.

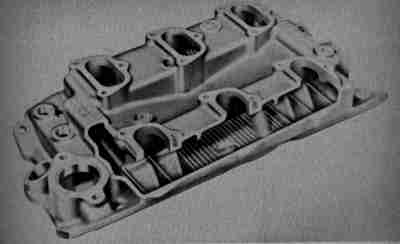

This Offenhauser 6x2 log manifold is similar to the Weiand, only with more

plenum volume and two end equalizer tubes instead of three middle equalizer

tubes. The log manifolds are much more efficient than they look; Diesel

engineers call the design an "anti-resonant intake". Any tuned intake has

antinodes where it works against you just as hard as it works for you; in most

cases the nodes and antinodes are both within the normal operating range. An

anti-resonant intake has no nodes or antinodes, so it has a flatter power

curve. The high internal turbulence also gives good fuel-air mixing. A

carburetor over each port pair means the accelerator pump shot drops straight

into the port, so the pump shot can be dramatically reduced; often with all

four end carburetors totalling less than a single four barrel, and the centers

with no pumps at all.

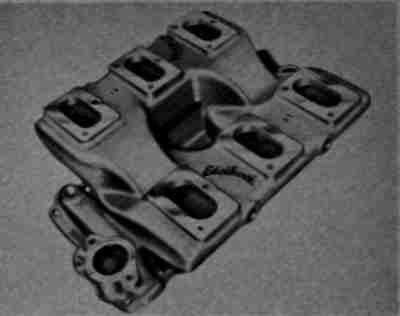

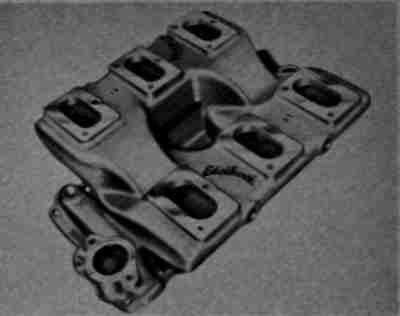

Early '60s Edelbrock "Ram Log" 6x2. Later Edelbrock changed them to 2x4s.

This one has the three-bolt Stromberg bolt pattern. For all practical

purposes it has the same geometry as the later tunnel ram intakes.

The Ram Log installed on a 283 on the dyno. That's Vic Sr. hisownself playing

with the throttle linkage. The engine pulled 284hp from 283 cubes.

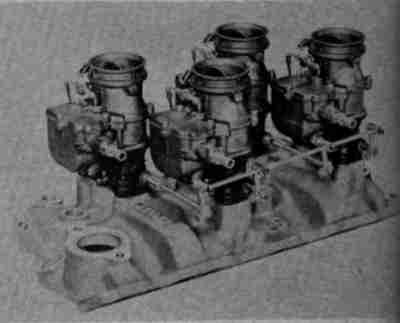

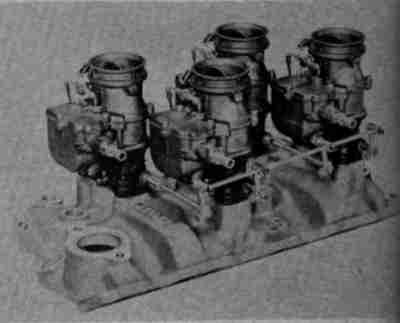

"Three deuce" intakes were the standard hot rod induction in the early days of

the small block. This one is made by Edelbrock and takes three Rochester

pattern carburetors.

This manifold is still in production as the Edelbrock C-357-B. Nostalgia

street rodders are about the only ones who buy it, but it's a practical,

economical street intake, at least for anyone who doesn't consider rebuilding

a simple two barrel Rochester to be the equivalent of brain surgery.

Late '50s Hilborn injection intake for the 283. An engine-driven pump and a

throttle-operated bypass valve gave RPM-TPS fuel control. They generally ran

well at idle and wide open, pig rich at midrange - but that was no problem for

a drag or salt car. Road racers made them work on closed circuits by adding

additional bypass valves.

Albert Gonzalez of Southern California made Algon fuel injection systems in

the '50s and '60s. The Algon worked similar to the Hilborn, except the

nozzles were individually adjustable.

Despite being available for a fairly wide range of engines, the Algon

injectors didn't sell well, partly due to a reputation as being hard to set up

properly. Most of them apparently wound up in marine applications.

Enderle mechanical injection intake, circa 1962. A tunnel ram with two

butterflies, it worked similar to the Hilborn and Algon systems. Contemporary

racers called it "The Flying Toilet Bowl."

Crower fuel injection from the mid'80s. This is a complete kit with a cam

driven fuel pump. This is their "Hi-Vel" model; they had a similar one

(taller manifold, shorter stacks) called the "Hi-Riser." Both are Hilborn

variants.

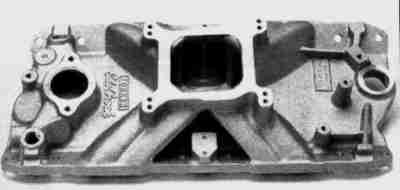

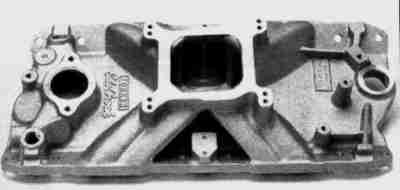

This is an Edelbrock Torker intake, probably the first of the X-planes. The

manifold runners met the heads at oblique angles, which didn't help airflow

one bit. Edelbrock made several variants under various names, as did other

manufacturers. Some had steps or ridges near the ports to break fuel loose

from the outboard runner walls. Not a good design, and I'm not sure why

Edelbrock even made them, as they certainly knew better. The X-plane craze

derailed manifold design for fifteen years or so until someone decided it

might be smarter to curve the ends of the runners to meet the heads straight-

on. Well, duh...

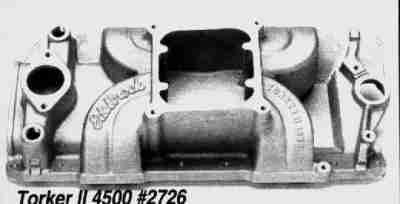

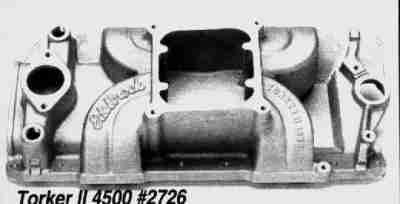

This is the Torker II, with the runners curved to eliminate the oblique angle

to the heads. Most single plane intakes are made like this now. Finally.

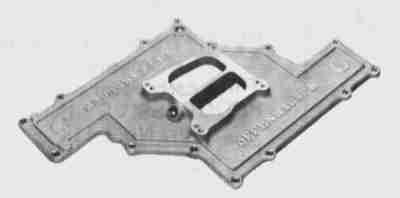

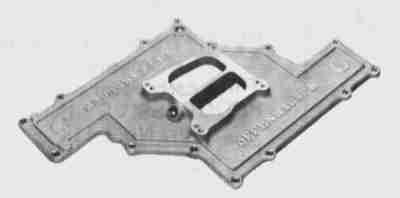

Hilborn makes this intake and distributor drive for the Dart/Buick symmetrical

port 18 degree heads.

This Offenhauser single plane mounts a single Holley Dominator. It always

looked like an interesting combination, but I've never even seen a picture of

one of these outside the Offy catalog.

Something just as unusual? How about a low-rise 2xQuadrajet intake? They

also made them in high rise configuration.

Offenhauser also made a ram log style intake for the small block. These also

work amazingly well when converted to fuel injection.

This Accel SuperRam intake came out in the late '80s. It was a very effective

upgrade over the pretty-but-restrictive Tuned Port manifold, but sales were

low due to high price.

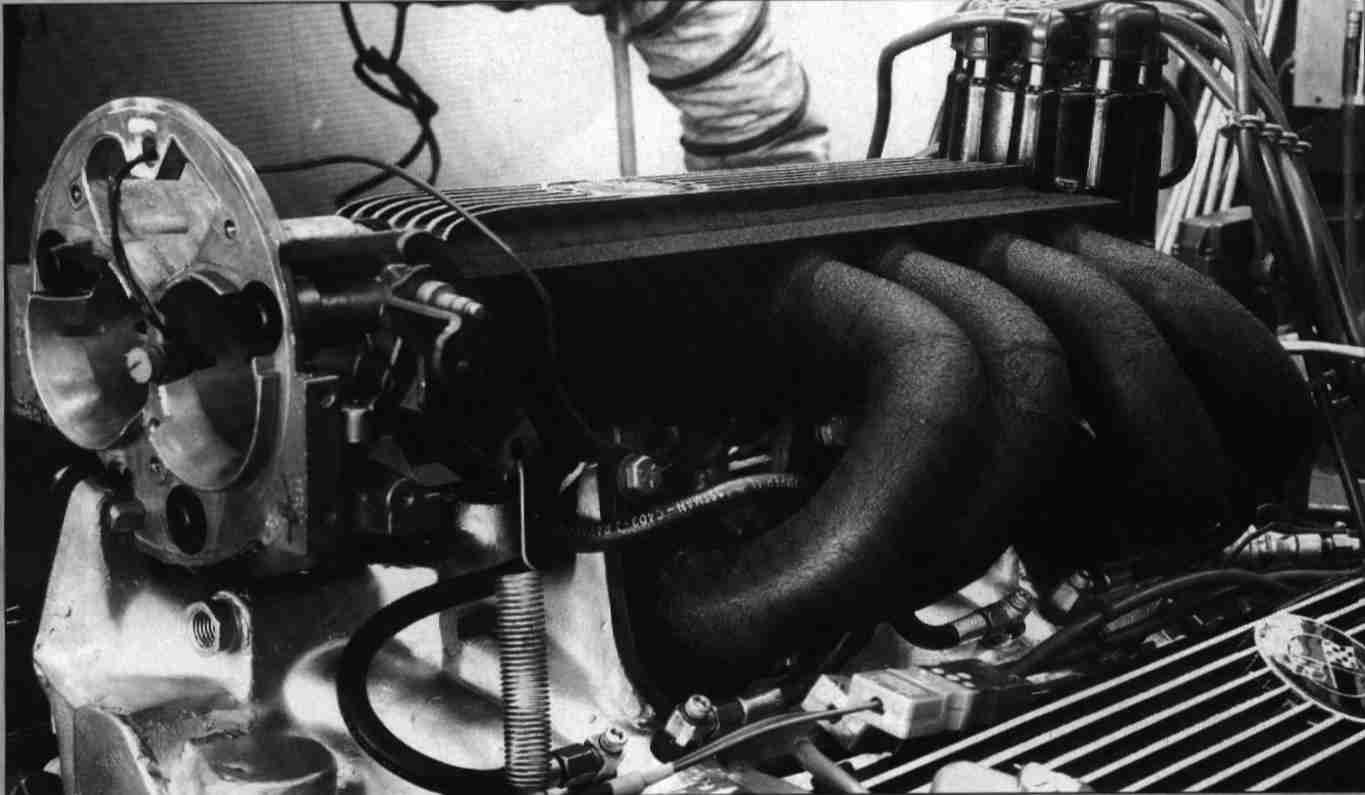

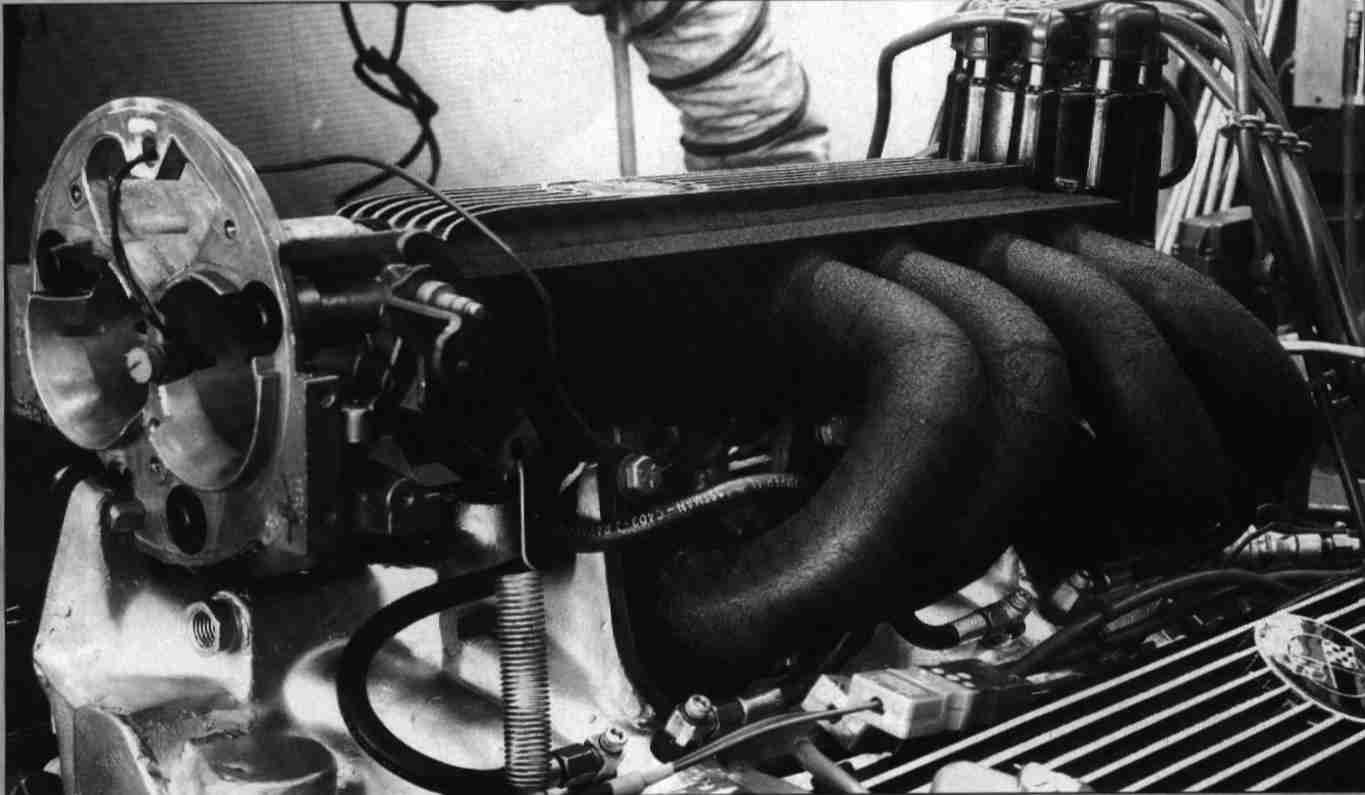

This image is in higher resolution than the others so I can point out a few

interesting details. I found this picture in an article on electronic fuel

injection, with a caption babbling about same. But let's look closely...

First, that's *not* a GM Tuned Port intake manifold. It's a cross-ram

manifold for Weber carburetors. The intake pipes are welded up from bits of

tubing. Those are old-style Corvette valve covers, and the plenum appears to

be fabricated around a third valve cover. The throttle body is made out of a

GM TBI part, notched to clear the intake. The engine is apparently on a dyno;

the little domino-like boxes visible over the near valve cover are standard

thermocouple adapters, and it looks like there's an inlet air temp

thermocouple in the throttle body.

The injectors are plainly visible... they're Hilborn "6A" mechanical fuel

injectors with the usual rubber pressure lines. The roundish object in the

right corner, between the runners and valve covers, appears to be a quick

change jet holder. I can't see the barrel valve anywhere, nor does there

appear to be a rod or cable coming off the throttle lever.

The magazine was from 1999. The image can't be any older than 1984 or 1985,

because that's the earliest those throttle bodies were available. Why hand

make a mechanical FI system that looked like a Tuned Port? Hmm...

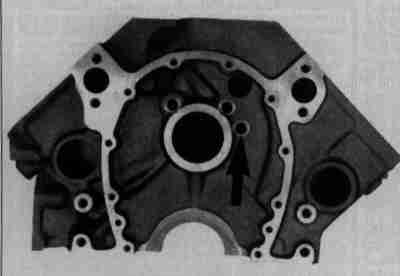

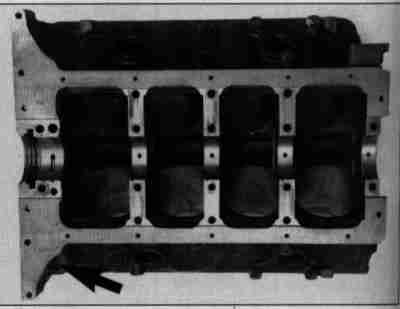

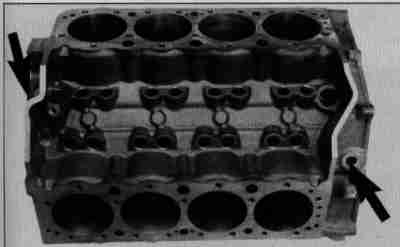

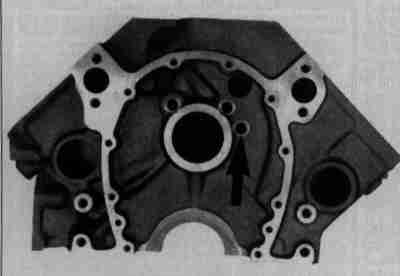

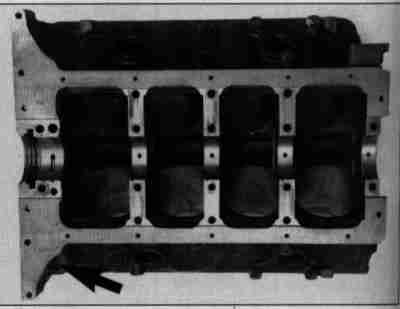

Small Block Blocks

"We are Chevrolet of GM. You have been assimilated."

Oldsmobile's racing division had to give up their small block, but that didn't

mean they were going to use the corporate-mandated Chevrolet without putting

their two bits in. Olds took a long look at the Chevy and its problems, which

its fans seldom admit to, and decided to do something about them.

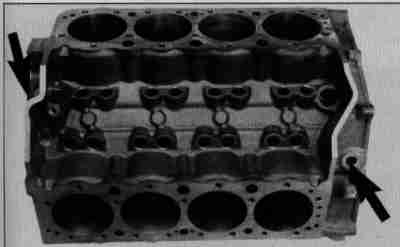

The mid'90s Olds 'Rocket' block was the outcome. Olds offered it in standard

Chevy 9.02" deck height and in a more-satisfactory 9.325" deck height, which

allowed longer rods, more stroke, or a lower pin height, depending on how you

wanted to build it. Olds claimed you could build the tall deck version out to

480 cubic inches.

The arrow points to the relocated main oil gallery. Instead of the usual

Chevrolet spine feeding around the cam bearings, the Rocket uses a setup

almost identical to the Ford Windsors.

Though it's not obvious from the picture, the camshaft tunnel has been raised

.391 inches for more rod clearance, and uses Chevrolet big block size cam

bearings to allow a larger base circle.

The Rocket's pan rails were spread .800" and straightened. Custom oil pans

are available through the aftermarket. Note the lack of an oil filter pad and

the dual starter flanges, so the starter can be relocated to the driver's side

for a kicked-out oil pan. The Rocket was designed for dry sump use, but it

will still accept a standard internal oil pump. The pan rails are wide enough

for a 4.125" stroke without clearancing.

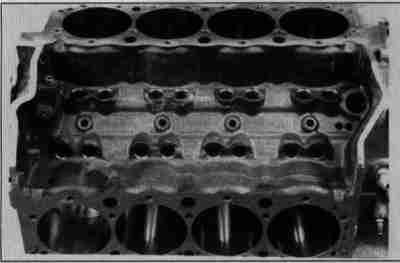

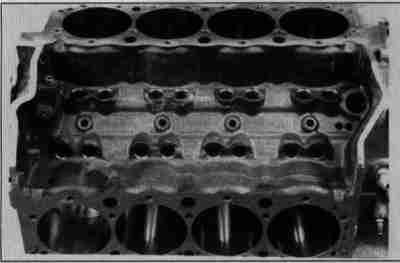

The Rocket's lifter valley is solid to assist in oil control when used with a

dry sump. The right arrow points to the lifter valley scavenge port, the left

to the boss that would connect the external dry sump pressure pump to the main

oil gallery.

This block was built for use with a wet sump, so oil return holes were drilled

in the lifter valley. The Rocket can be safely bored out to 4.190" with

.275" wall thickness. The bores are siamesed.

Cloyes and Jesel make the special long timing sets to match the raised cam.

Most major cam grinders can supply cams for the Rocket. The Rocket cam uses

the small block nose with the big block bearing size.

The Rocket sold for $1700 in 1995. A bit more than the Chevrolet Bow Tie

block, but a lot better part.

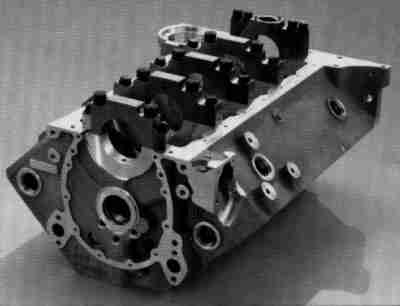

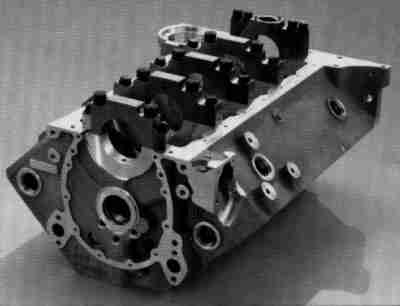

Donovan makes these aluminum blocks with up to 1/2" higher decks and with

spread pan rails for long strokes. It's one of the few with four bolt caps at

#1 and #5.

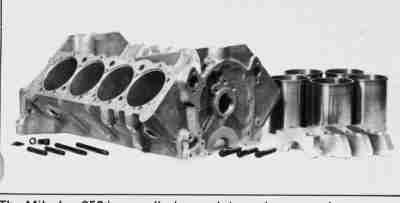

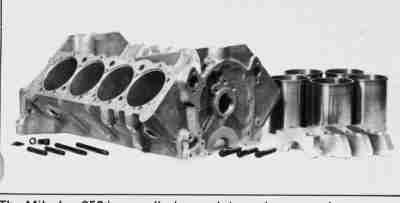

Milodon aluminum block, circa 1985. Weight was 83 pounds without main studs.

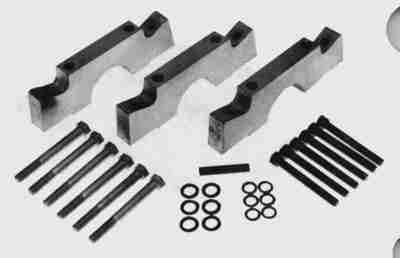

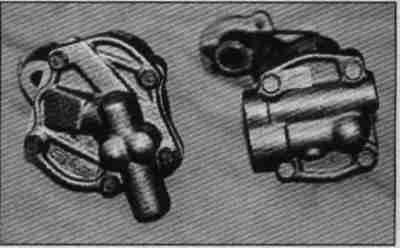

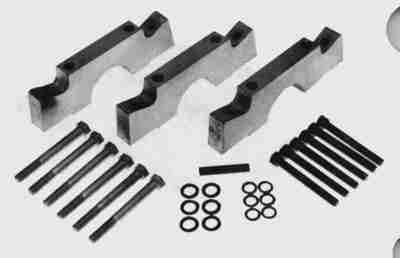

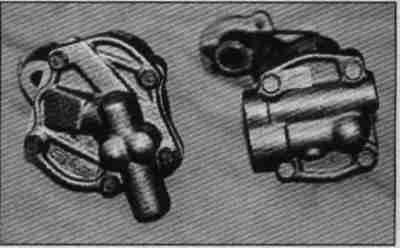

Main cap upgrade kit. This particular kit converts a large journal block to

steel angle-type four bolt caps. There are many of these kits, with straight

or angled bolts, iron, steel, or aluminum caps, etc.

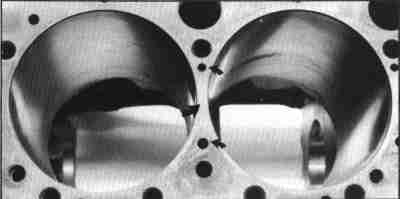

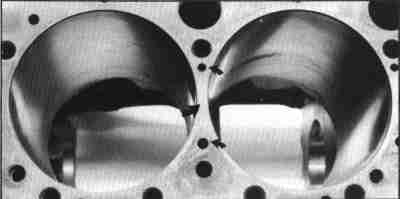

This is a production 400 block with the steam holes you've probably read

about. There are matching holes in the heads, even if they're otherwise the

same as 350 heads. Since the bores are siamesed there are air pockets where

water would not normally get to without the bleed holes.

Small Block Oiling System

This unusual oil pump pickup was on a professionally-built Trans Am Z-28.

Note safety wire on pump bolt.

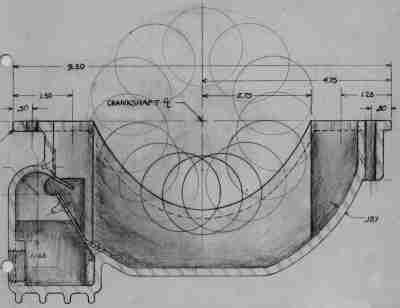

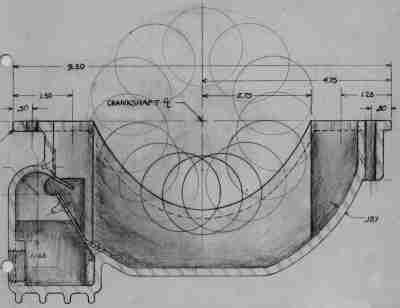

Nice sketch of a pocket-type dry sump pan from ARE. Pans of this type usually

run the pocket full length and require a reversed or driver's-side starter.

Milodon dry sump pan. This one doesn't have the kick-out, but it incorporates

a scraper and a screen to break up the scraped oil stream.

Oil restrictor plug kit. These screw into the back of the block into the

lifter galleries and restrict the oil flow to the lifters and pushrods, and

thence the top end. Orifice size varies from .060 to .110" depending on the

brand and application. Sizes below .100" are usually not compatible with

hydraulic lifters.

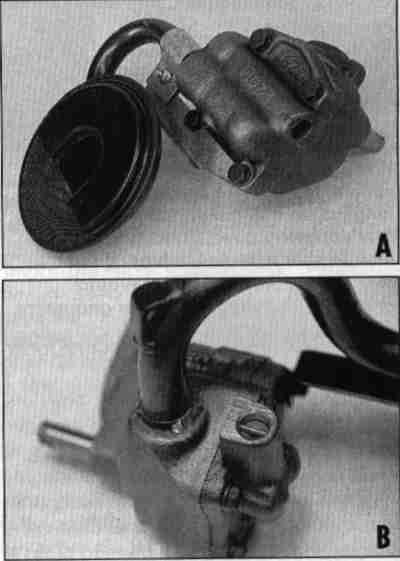

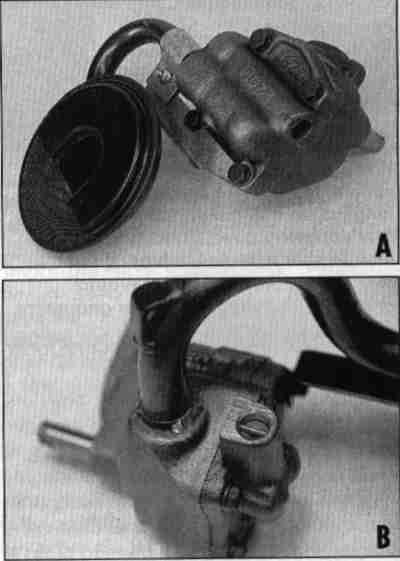

An excellent racing pump setup. The pump is extended down into the sump with

a spacer block so it doesn't have to suck oil up through a long tube. The

pickup tube is dumped in favor of a new pump cover that moves oil straight

from the sump to the pump gears. The whole thing is held to the main cap with

a 7/16" stud and nut and driven by an extra-long driveshaft.

Milodon, Moroso, and others make bits to do this. It's about as good as it

gets for wet sump stuff.

This pump is available from Callies. It eliminates the separate pickup and

has an external screw to adjust oil pressure.

The five bolt big block pump will bolt right on in place of the four bolt

small block pump. It pumps more oil than the small block pump, which is

usually not needed, but its advocated claim it is easier on the distributor

gears and cam chain because it has more teeth and the load doesn't fluctuate

as much as with the small block pump.

Most racers positively retain the stock oil pickup by brazing, welding, or

bolted brackets. The bracket in the upper photo is "The Loop" from Chenault

Specialty Company.

The pickup can't suck its way down to the pan and cut off oil flow, but a

poorly-retained one might sag over time or you might hit some track debris and

smash the pan up against the pickup. Using some sort of positive spacer, like

these welded nuts, guarantees clearance between the pan and pickup.

Small Block Exhaust Manifolds

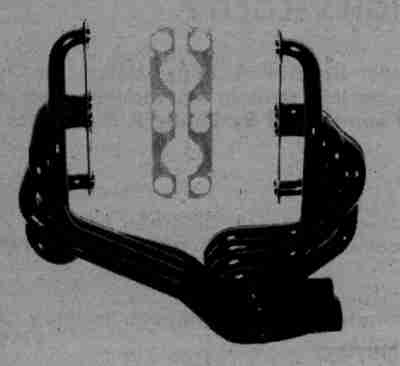

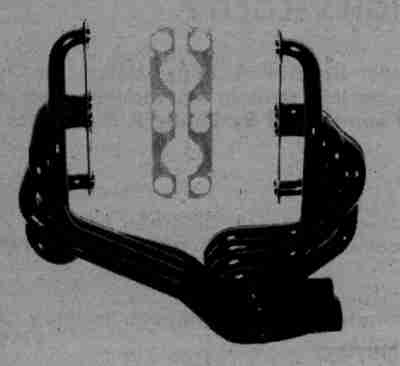

How about a nice 180 degree header from Schoenfeld? Only $159 circa 1983.

They're for an oval tracker, but they'd work well for a mid engine car or a

boat installation.

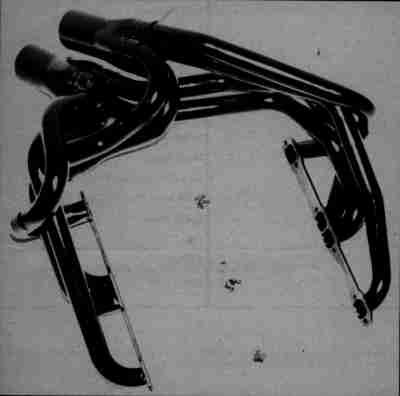

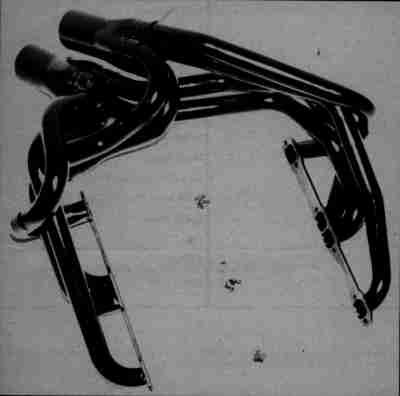

Here's another, with a more rearward exit.

Small Block Miscellaneous Bits

This left-side starter conversion was developed in Australia for steering box

clearance for 4wd conversions. Something like that would be really nice if

you wanted to run a full-length kickout on the oil pan!

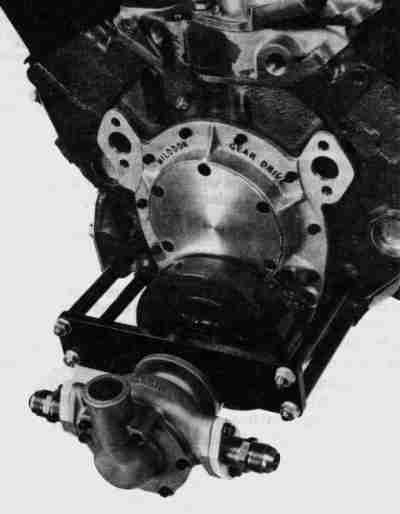

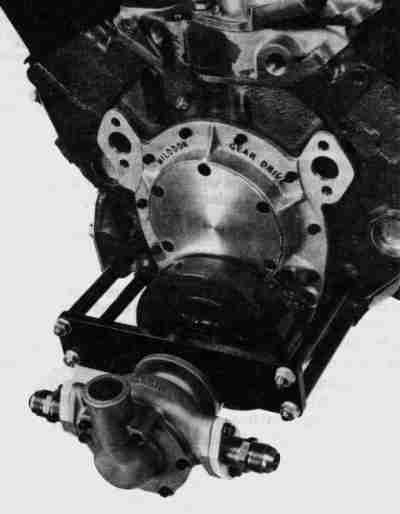

Crank-drive water pump from Milodon, circa 1984.

This cute little device was made by Barrett Engineering in the mid '90s. It's

a combination water pump and alternator. Max 32 amps.

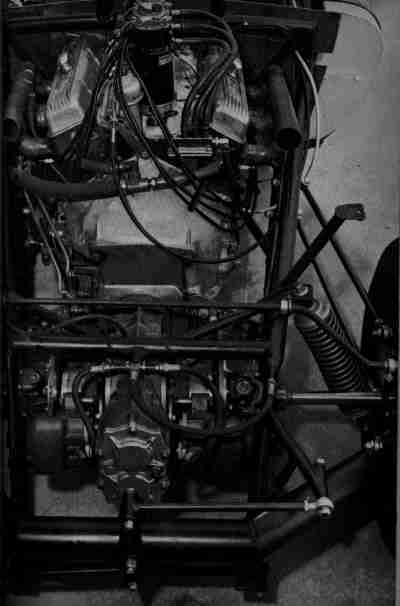

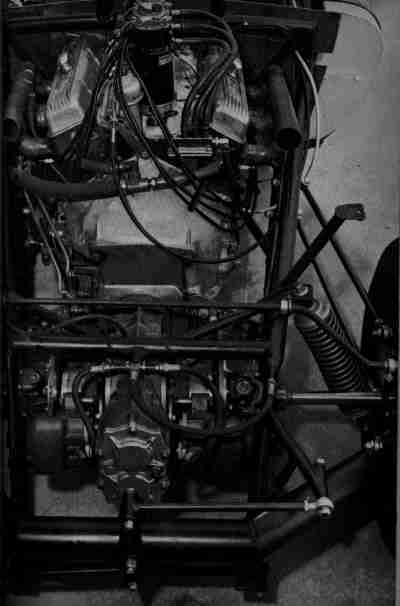

Twin-engined dragster circa early '60s. McCulloch centrifugal superchargers

were very unusual.

Howard Johansen's "Real Gone Gasser" from the early '60s. Scott fuel

injectors, chain driven GMC superchargers. Cogged belts didn't become popular

until later; back in those days chains or multiple rows of V-belts were the

rule. The engine on the right is reversed; power takeoff is on the firewall

side of both engines.

Years before Carroll Shelby dropped 289 engines into Cooper Formula cars to

make his King Cobras, hot rodders were dropping the small Chevy into the

lightweight Coopers. This particular chassis originally carried a J.A.P. V-

twin motorcycle engine.

Potvin front-mount blower setup from the 1950s. Low profile, low CG, no long

floppy belts or chains. Moon still sells them today. That's an old

Dragmaster chassis.

-EOF-