I'm still finding pictures here and there, so I'll update the page from time to time. Yes, it really has been eight years that I've been looking for round tuits...

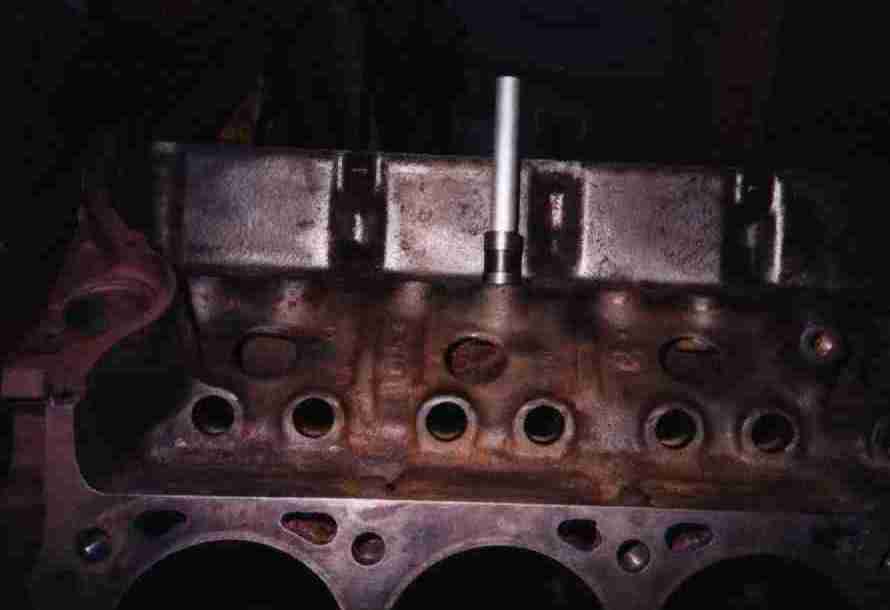

289 block used in the build. The main webs are being slotted to oil the

entire top half of the main bearings, which have extra holes drilled in

them to allow more oil to get to the crank.

289 block used in the build. The main webs are being slotted to oil the

entire top half of the main bearings, which have extra holes drilled in

them to allow more oil to get to the crank.

I thought this one up myself. It turned out the old Chevy Power manual from

GM recommended it, and lots of modern engines come that way from the factory.

Well, at least I was on the right track...

Rotating and Reciprocating Assemblies...

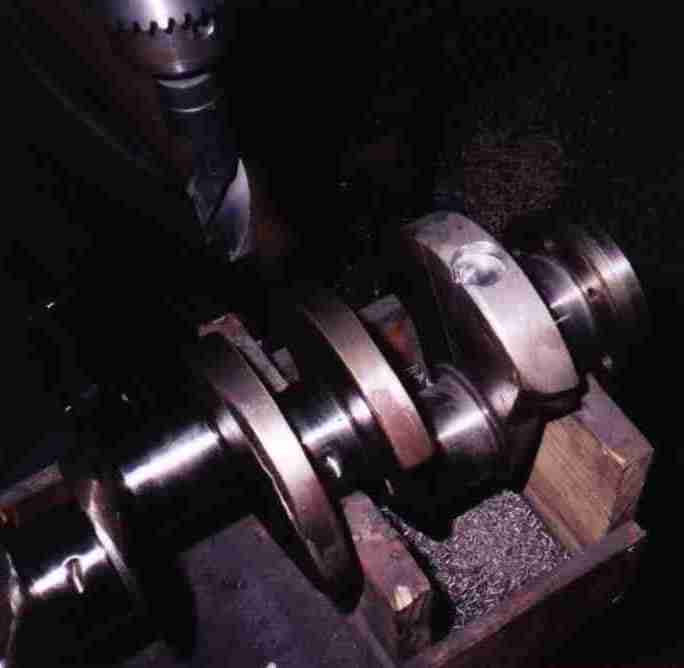

Ordinary 28oz 302 crankshaft. The first step was to turn the counterweights

down round to reduce weight and windage. Then it got radiused and polished

before being ground to large journal Chevy size on the rod throws. Somehow I

failed to take pictures of all this...

Ordinary 28oz 302 crankshaft. The first step was to turn the counterweights

down round to reduce weight and windage. Then it got radiused and polished

before being ground to large journal Chevy size on the rod throws. Somehow I

failed to take pictures of all this...

5.56" Chevy 400 small block rods, lightened and polished. They're a half inch

longer than the stock 302 rods. These haven't been narrowed to fit the Ford

crank yet.

5.56" Chevy 400 small block rods, lightened and polished. They're a half inch

longer than the stock 302 rods. These haven't been narrowed to fit the Ford

crank yet.

Matching individual rod shanks and caps by weight. It took ten shanks and

twelve caps to make eight matched rods; some combinations did not line up well

enough for the rods to be resized.

Matching individual rod shanks and caps by weight. It took ten shanks and

twelve caps to make eight matched rods; some combinations did not line up well

enough for the rods to be resized.

Nowadays I'd just collect more rods until I matched up eight that were the way

I wanted.

Keith Black hypereutectic pistons, 1.14" pin height. They're for a 6" rod 383

Chevy. The domes have to be reprofiled to fit Ford combustion chambers. I

used a safe-edge file and a lot of time; next time I'll build a fixture and

use a router.

Keith Black hypereutectic pistons, 1.14" pin height. They're for a 6" rod 383

Chevy. The domes have to be reprofiled to fit Ford combustion chambers. I

used a safe-edge file and a lot of time; next time I'll build a fixture and

use a router.

Parts have been coated, ready for baking. There's more here than just TRX; I

usually batch coating jobs if I can.

Parts have been coated, ready for baking. There's more here than just TRX; I

usually batch coating jobs if I can.

Balancing...

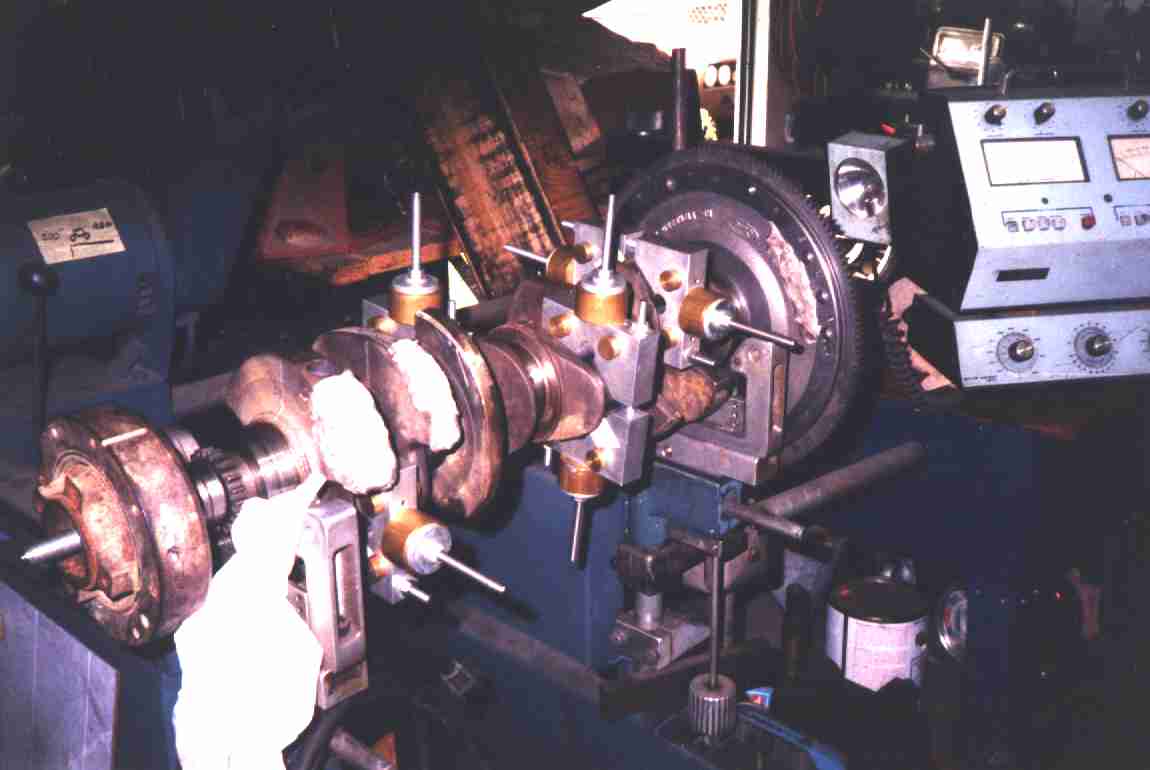

This is the rotating assembly. It was already balanced by Crankshaft

Specialist in Memphis. See the huge wads of modeling clay on the

counterweights? That's why I now own my own balancing machine.

This is the rotating assembly. It was already balanced by Crankshaft

Specialist in Memphis. See the huge wads of modeling clay on the

counterweights? That's why I now own my own balancing machine.

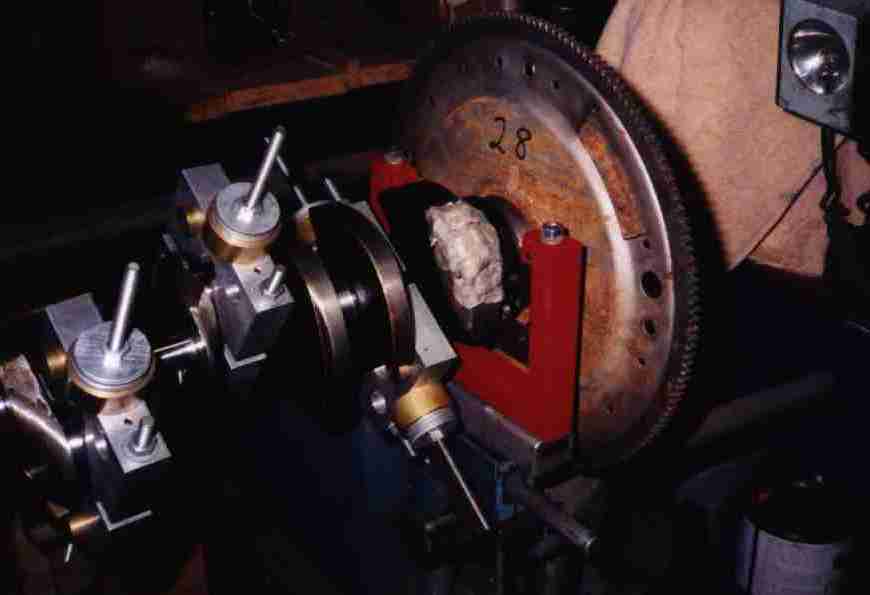

Here's the other end. The assclowns in Memphis weren't even in the ballpark,

much less close. It took several ounces of lead fill to bring this thing into

balance.

Here's the other end. The assclowns in Memphis weren't even in the ballpark,

much less close. It took several ounces of lead fill to bring this thing into

balance.

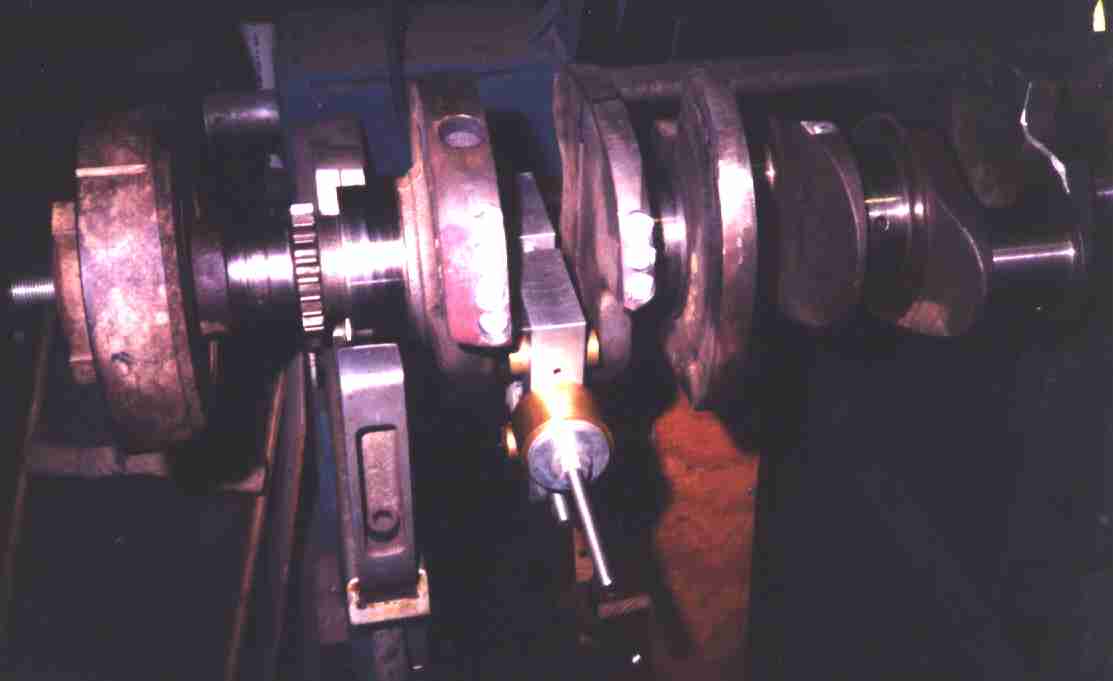

The balance machine said more weight was needed here. The first step

is to drill out some iron to make room for something heavier.

The balance machine said more weight was needed here. The first step

is to drill out some iron to make room for something heavier.

One pot of molten lead. It's not as dense as "Mallory metal" (a tungsten

alloy) but it's a whole lot cheaper - almost free, vs. up to $20 per piece for

Mallory. Most balance jobs will come out with just lead; you usually know

when you first spin it up if you'll need Mallory or if lead will do. I use old

wheelweights from a local tire store.

One pot of molten lead. It's not as dense as "Mallory metal" (a tungsten

alloy) but it's a whole lot cheaper - almost free, vs. up to $20 per piece for

Mallory. Most balance jobs will come out with just lead; you usually know

when you first spin it up if you'll need Mallory or if lead will do. I use old

wheelweights from a local tire store.

Lead poured in, tamped flat with a drift, ready for steel plug to be welded

over. The crank took two 1" fills in back and two in front, with a three

additional 1/2" in front.

Lead poured in, tamped flat with a drift, ready for steel plug to be welded

over. The crank took two 1" fills in back and two in front, with a three

additional 1/2" in front.

There's lead in the front counterweight. It wasn't enough, so more went in

the second counterweight. Steel plugs are welded over the holes; these

haven't been ground flush yet. It gets spun again to see how close it is

before detailing will begin. After everything is welded, ground, and

smoothed, it gets a last spin.

There's lead in the front counterweight. It wasn't enough, so more went in

the second counterweight. Steel plugs are welded over the holes; these

haven't been ground flush yet. It gets spun again to see how close it is

before detailing will begin. After everything is welded, ground, and

smoothed, it gets a last spin.

The finished crank; lightened, balanced, and polished. You can't see it well

in this picture, but there are 5/8" long lead-in slots ground ahead of the oil

holes on the mains, and all the corners in the oilways were radiused with a

Dremel with a long ball-end bit.

The finished crank; lightened, balanced, and polished. You can't see it well

in this picture, but there are 5/8" long lead-in slots ground ahead of the oil

holes on the mains, and all the corners in the oilways were radiused with a

Dremel with a long ball-end bit.

Oiling...

Milodon T-sump pan I got from Millam Tackitt. I traded him a Cadillac engine

for it. I cut .040" steel strips and welded them in canted against the

direction of crank rotation to catch and divert oil thrown off the crank.

Milodon T-sump pan I got from Millam Tackitt. I traded him a Cadillac engine

for it. I cut .040" steel strips and welded them in canted against the

direction of crank rotation to catch and divert oil thrown off the crank.

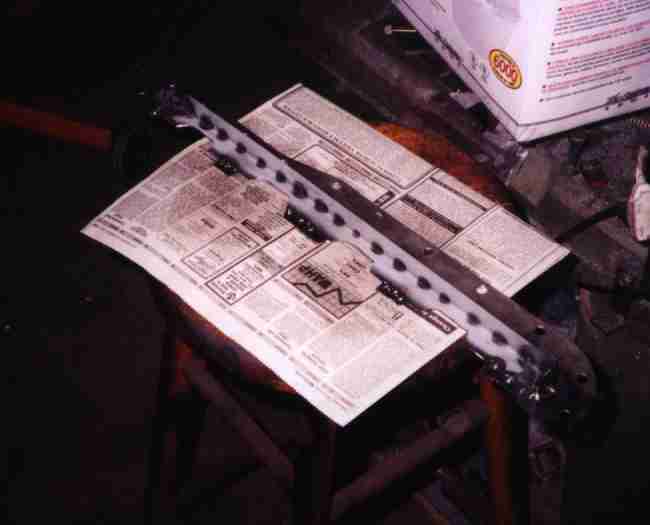

.040" steel crank scraper. Notice how much wider it is than a Chevy scraper;

lots of room in a Ford crankcase. This one's wider than an ordinary Ford one

would be since the counterweights on the crank were turned down.

.040" steel crank scraper. Notice how much wider it is than a Chevy scraper;

lots of room in a Ford crankcase. This one's wider than an ordinary Ford one

would be since the counterweights on the crank were turned down.

As the oil is scraped off, it's directed right to the oil pan gasket. I

figured this would not necessarily be a good thing, so I made a secondary

deflector to keep it from impinging directly on the gasket.

As the oil is scraped off, it's directed right to the oil pan gasket. I

figured this would not necessarily be a good thing, so I made a secondary

deflector to keep it from impinging directly on the gasket.

Finished scraper in place. Note heated and bent oil pickup tube; the high

volume pump is longer and puts the tube in a different spot where it will hit

the bottom of the pan, so it has to be modified.

Finished scraper in place. Note heated and bent oil pickup tube; the high

volume pump is longer and puts the tube in a different spot where it will hit

the bottom of the pan, so it has to be modified.

Cylinder Heads...

Manley one-piece valves were reworked on the lathe. The fronts of the intakes

were grooved to reduce reversion at low lift. Same with the backs of the

exhaust valves, though you can't see it in this shot. Fronts of the exhaust

valves were radiused. Then they got sandblasted and ceramic coated.

Manley one-piece valves were reworked on the lathe. The fronts of the intakes

were grooved to reduce reversion at low lift. Same with the backs of the

exhaust valves, though you can't see it in this shot. Fronts of the exhaust

valves were radiused. Then they got sandblasted and ceramic coated.

Combustion chambers were polished shiny, then sandblasted and ceramic coated.

The heads were milled .060", extensively ported on the exhaust side, and

pocket ported on the intake side. The combustion chambers have also been

flattened and laid back at the valve seats to unshroud the valves at low lift.

It's not a super-duper-race porting job, but it'll do.

Combustion chambers were polished shiny, then sandblasted and ceramic coated.

The heads were milled .060", extensively ported on the exhaust side, and

pocket ported on the intake side. The combustion chambers have also been

flattened and laid back at the valve seats to unshroud the valves at low lift.

It's not a super-duper-race porting job, but it'll do.

Exhaust ports were coated too. You can see some of the reshaping work here.

Exhaust ports were coated too. You can see some of the reshaping work here.

Cheap stud girdles wouldn't fit under the valve covers. I can't remember

where I ordered them from, now. They had to have recesses carved and corners

rounded; when they came in, they were just straight bars of aluminum.

Cheap stud girdles wouldn't fit under the valve covers. I can't remember

where I ordered them from, now. They had to have recesses carved and corners

rounded; when they came in, they were just straight bars of aluminum.

Induction System...

Hilborn fuel injection. It is a brand new 1972 manufacture unit; the

original owner died before he installed it. I had originally planned to just

use the manifold and convert to EFI, but I'm going to use the original

mechanical system with a "de-jector" valve plumbed into the fuel bypass to

control mixture. The de-jector is a 55# fuel injector in parallel with the

Hilborn's bypass pill. It is driven by a BASIC Stamp microcontroller and an

ordinary O2 sensor. At part throttle it keeps the engine at stoichiometric

using the O2 for feedback, leaning out the rich Hilborn midrange as needed.

At full throttle a sealed Cherry switch tells the Stamp to stop de-jecting and

let the main pill control the WOT mixture. I'll put up a page about that as I

make more progress, along with details on the airbox, etc.

Hilborn fuel injection. It is a brand new 1972 manufacture unit; the

original owner died before he installed it. I had originally planned to just

use the manifold and convert to EFI, but I'm going to use the original

mechanical system with a "de-jector" valve plumbed into the fuel bypass to

control mixture. The de-jector is a 55# fuel injector in parallel with the

Hilborn's bypass pill. It is driven by a BASIC Stamp microcontroller and an

ordinary O2 sensor. At part throttle it keeps the engine at stoichiometric

using the O2 for feedback, leaning out the rich Hilborn midrange as needed.

At full throttle a sealed Cherry switch tells the Stamp to stop de-jecting and

let the main pill control the WOT mixture. I'll put up a page about that as I

make more progress, along with details on the airbox, etc.

The Hilborn won't be entirely satisfactory on the street even with the active

fuel control; the injector nozzles are vented to atmosphere, for example, and

you'll always smell gas after you shut the car off. And starting will always

require cranking a bit. The Hilborn's fuel lines loop up over the injectors,

and when you shut the engine off the fuel runs down into the ports, flooding

the motor. So I'll be adding a "turbo timer" doohickey that will let the

engine run a few seconds after turning off the key and closing the fuel

solenoid. That will use up most of the fuel in the lines. Crude, but hey,

it's a prehistoric system never intended for street use; you have to put up

with "features".

The Hilborn won't be entirely satisfactory on the street even with the active

fuel control; the injector nozzles are vented to atmosphere, for example, and

you'll always smell gas after you shut the car off. And starting will always

require cranking a bit. The Hilborn's fuel lines loop up over the injectors,

and when you shut the engine off the fuel runs down into the ports, flooding

the motor. So I'll be adding a "turbo timer" doohickey that will let the

engine run a few seconds after turning off the key and closing the fuel

solenoid. That will use up most of the fuel in the lines. Crude, but hey,

it's a prehistoric system never intended for street use; you have to put up

with "features".

The long stacks won't be used, of course. The new stacks are only 2.5" tall

to allow adequate clearance inside the airbox, and clearance between the

airbox and hood. There is also a distributor fangle involved - the airbox

won't clear the distributor cap. So... get rid of the cap. My buddy Doug

Glosson has worked up a nifty deal to use four optical pickups mounted to the

distributor breaker plate, each one driving a single two-lead GM coil pack.

Four coil packs, eight plugs. It will look like a distributorless system, but

it'll actually be a hybrid, sort of like the 'de-jected' Hilborn.

The long stacks won't be used, of course. The new stacks are only 2.5" tall

to allow adequate clearance inside the airbox, and clearance between the

airbox and hood. There is also a distributor fangle involved - the airbox

won't clear the distributor cap. So... get rid of the cap. My buddy Doug

Glosson has worked up a nifty deal to use four optical pickups mounted to the

distributor breaker plate, each one driving a single two-lead GM coil pack.

Four coil packs, eight plugs. It will look like a distributorless system, but

it'll actually be a hybrid, sort of like the 'de-jected' Hilborn.

Since the original dead 302 was still in the RX7, I dropped the Hilborn in

place to make a clearance test.

Since the original dead 302 was still in the RX7, I dropped the Hilborn in

place to make a clearance test.

Knot of clay on top of 2x4 shows the clearance. Allowing room for the engine

to move on its mounts, I have 4" at the front for the airbox. The RX hood

slopes down sharply at the front, and the 302 slants shallowly to the back, so

there's all kinds of clearance back by the firewall.

Knot of clay on top of 2x4 shows the clearance. Allowing room for the engine

to move on its mounts, I have 4" at the front for the airbox. The RX hood

slopes down sharply at the front, and the 302 slants shallowly to the back, so

there's all kinds of clearance back by the firewall.

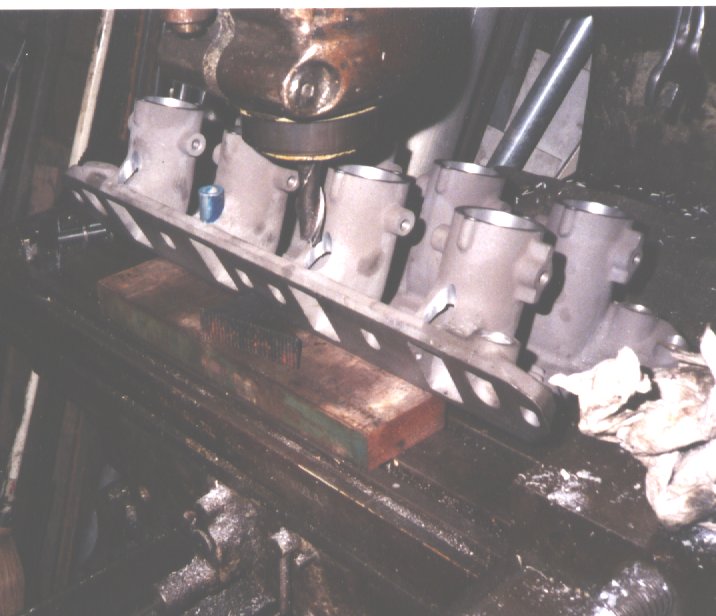

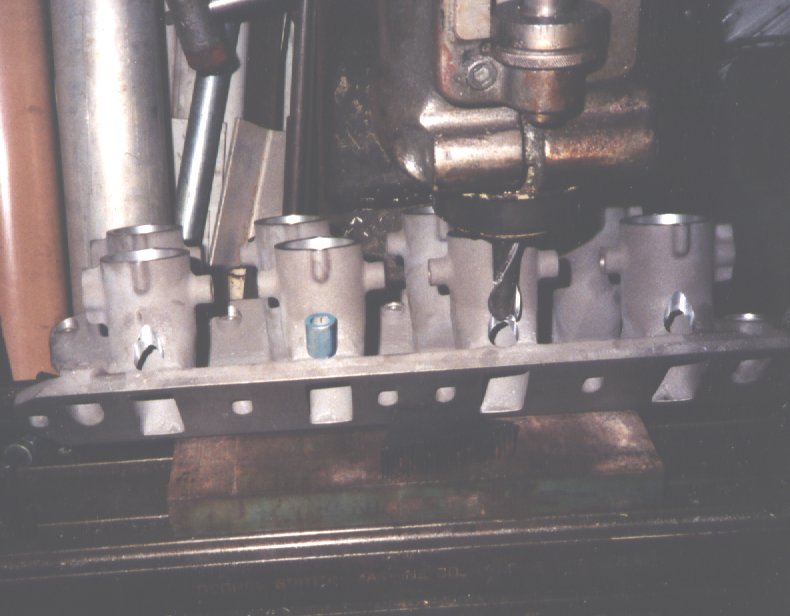

Expensive Hilborn intake has a date with the milling machine. I canted the

injector bungs to clear the valve covers on one side and the airbox adapters

on the other.

Expensive Hilborn intake has a date with the milling machine. I canted the

injector bungs to clear the valve covers on one side and the airbox adapters

on the other.

The bungs are centered in the ports; it's just the angle of the shot

that makes them look offset.

The bungs are centered in the ports; it's just the angle of the shot

that makes them look offset.

GM IAC for the 7730 ECM, vacuum distribution block, copper tubing, and a bunch

of fittings. Vacuum is collected and averaged from all eight intake ports,

below the Hilborn butterflies, for the MAP sensor, power brake booster, and

Idle Air Control.

GM IAC for the 7730 ECM, vacuum distribution block, copper tubing, and a bunch

of fittings. Vacuum is collected and averaged from all eight intake ports,

below the Hilborn butterflies, for the MAP sensor, power brake booster, and

Idle Air Control.

Distribution block bolts up against bottom of intake. The IAC is mounted on

top, with holes through the intake to pass air from one to the other. I just

grabbed the first chunk of aluminum I found; later I scoped out some much

cleaner solutions, but by then I'd finished the first one.

Distribution block bolts up against bottom of intake. The IAC is mounted on

top, with holes through the intake to pass air from one to the other. I just

grabbed the first chunk of aluminum I found; later I scoped out some much

cleaner solutions, but by then I'd finished the first one.

Compression fittings on bottom of intake. I drilled and tapped 1/4 NPT,

screwed them in with epoxy, then epoxied around the hexes.

Compression fittings on bottom of intake. I drilled and tapped 1/4 NPT,

screwed them in with epoxy, then epoxied around the hexes.

Saw up a bunch of 3/4" aluminum tubing...

Saw up a bunch of 3/4" aluminum tubing...

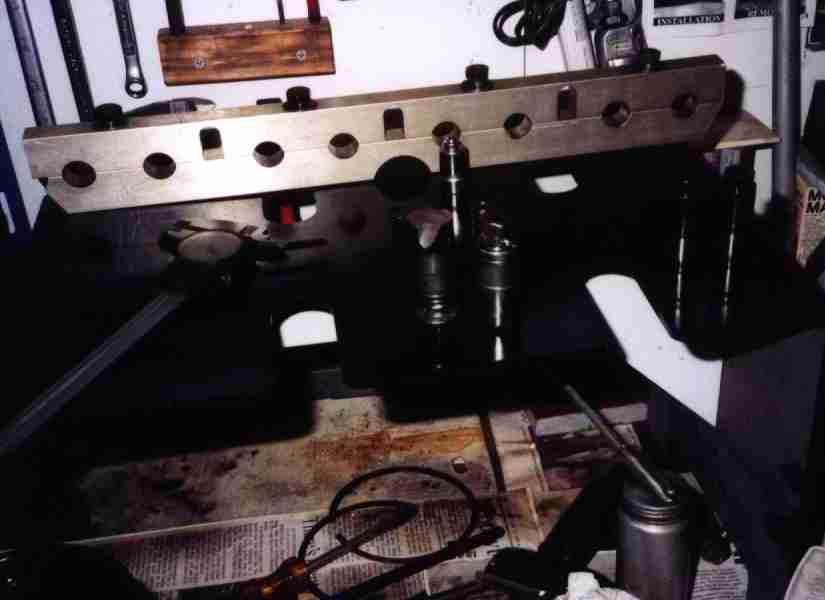

Face to length, chamfer the outside ends, radius with deburr tool, then bore

to size with boring bar.

Face to length, chamfer the outside ends, radius with deburr tool, then bore

to size with boring bar.

I fired up the MIG welder, but the heavy aluminum casting and thinwall tubes

were beyond my skill. Even preheating with a propane torch, I vaporized a lot

of wire.

I fired up the MIG welder, but the heavy aluminum casting and thinwall tubes

were beyond my skill. Even preheating with a propane torch, I vaporized a lot

of wire.

Once it became apparent that the bungs were firmly attached, even if not

airtight, I ground the globby aluminum worms into some semblance of neatness,

cleaned everything again, and used epoxy to seal everything up.

Once it became apparent that the bungs were firmly attached, even if not

airtight, I ground the globby aluminum worms into some semblance of neatness,

cleaned everything again, and used epoxy to seal everything up.

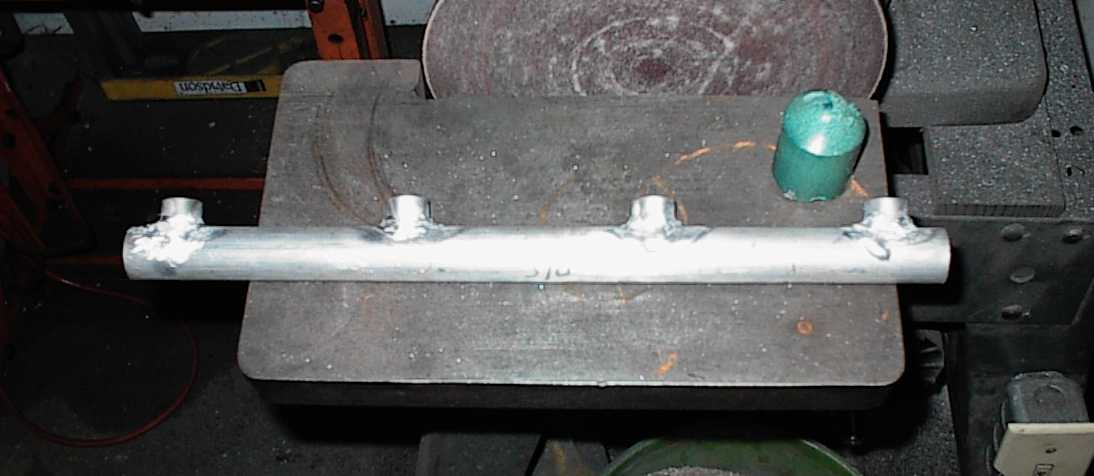

After the manifold bungs were welded in, I marked off the corresponding bung

holes in the fuel rails. I used 1" 6061 tubing for the rails, with the bungs

MIGged and aluminum soldered in place. I don't have the trick with the solder

at all, unfortunately. But they won't leak, anyway.

After the manifold bungs were welded in, I marked off the corresponding bung

holes in the fuel rails. I used 1" 6061 tubing for the rails, with the bungs

MIGged and aluminum soldered in place. I don't have the trick with the solder

at all, unfortunately. But they won't leak, anyway.

Intake base. Aluminum plates on the bottom are drilled and countersunk to

bolt to the original stack mounting holes. Steel plates bolt to the aluminum

plates. The original purpose of all this was to do a long tube crossram

setup, with plenums crossing over each valve cover. I finally decided it was

more time and money than I wanted to get into, so I'm just building an

aluminum airbox to bolt on top.

Intake base. Aluminum plates on the bottom are drilled and countersunk to

bolt to the original stack mounting holes. Steel plates bolt to the aluminum

plates. The original purpose of all this was to do a long tube crossram

setup, with plenums crossing over each valve cover. I finally decided it was

more time and money than I wanted to get into, so I'm just building an

aluminum airbox to bolt on top.

Carbide blade on the circular saw makes short work of 1/8" aluminum plate.

Carbide blade on the circular saw makes short work of 1/8" aluminum plate.

Assembly...

Checking the deck height. After having the block milled, the pistons are

.003-.005" proud of the deck.

Checking the deck height. After having the block milled, the pistons are

.003-.005" proud of the deck.

A couple of lifters didn't want to go in when I was putting it together for

the last time. There were burrs on the bottoms of their bores, it happens

sometimes if someone got stupid beating the lifters out on disassembly.

I made this tool from an old lifter. Pack the grooves with grease to catch

the shavings, turn with a wrench. I really didn't want to pull the thing back

apart again.

A couple of lifters didn't want to go in when I was putting it together for

the last time. There were burrs on the bottoms of their bores, it happens

sometimes if someone got stupid beating the lifters out on disassembly.

I made this tool from an old lifter. Pack the grooves with grease to catch

the shavings, turn with a wrench. I really didn't want to pull the thing back

apart again.

I also made this handy gage tool while I was at it. An old lifter epoxied to

a piece of aluminum rod; now I just pop it into each hole to make sure

everything is okay before beginning assembly.

I also made this handy gage tool while I was at it. An old lifter epoxied to

a piece of aluminum rod; now I just pop it into each hole to make sure

everything is okay before beginning assembly.

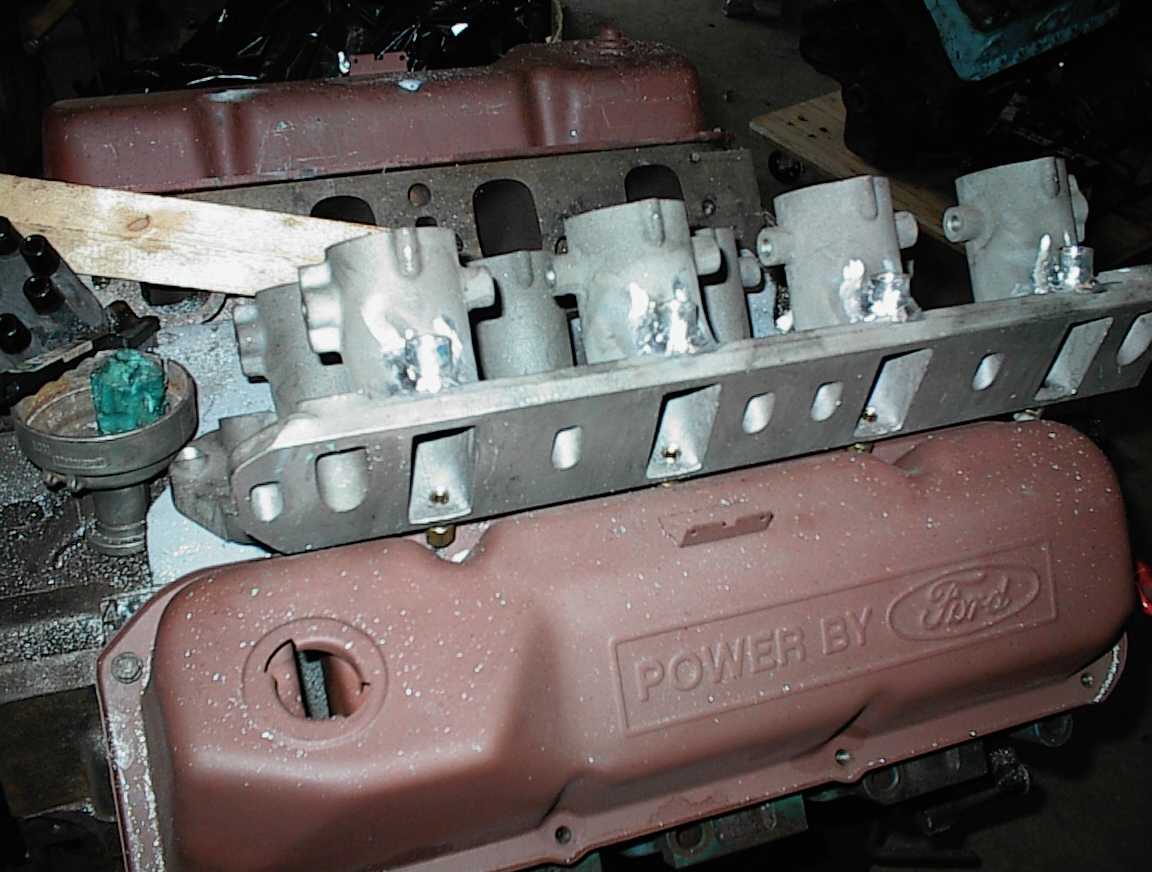

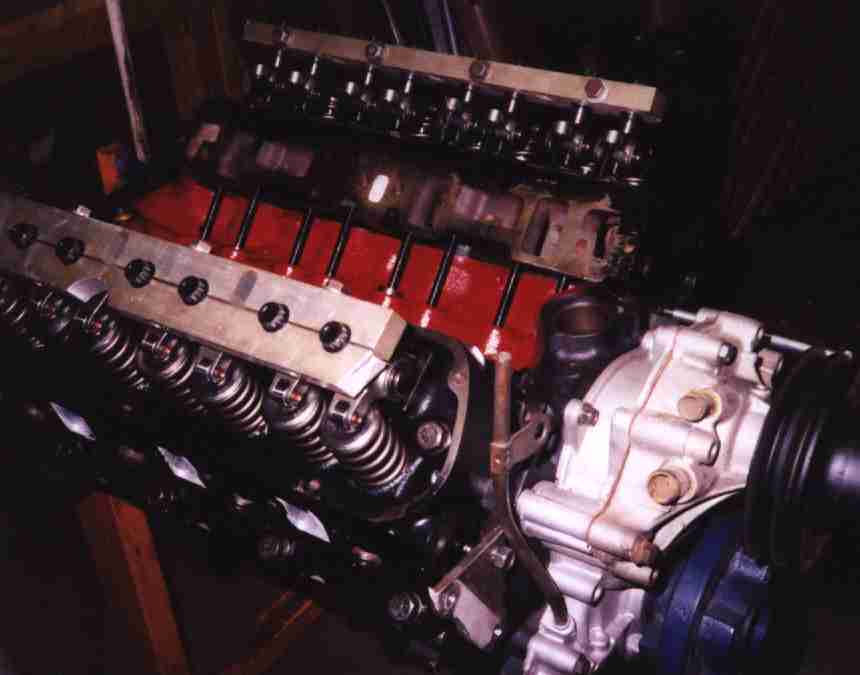

Assembled short block. Paint is red Rust-Oleum. You'll see paint/no-paint in

the pictures; there were several trial fits.

Assembled short block. Paint is red Rust-Oleum. You'll see paint/no-paint in

the pictures; there were several trial fits.

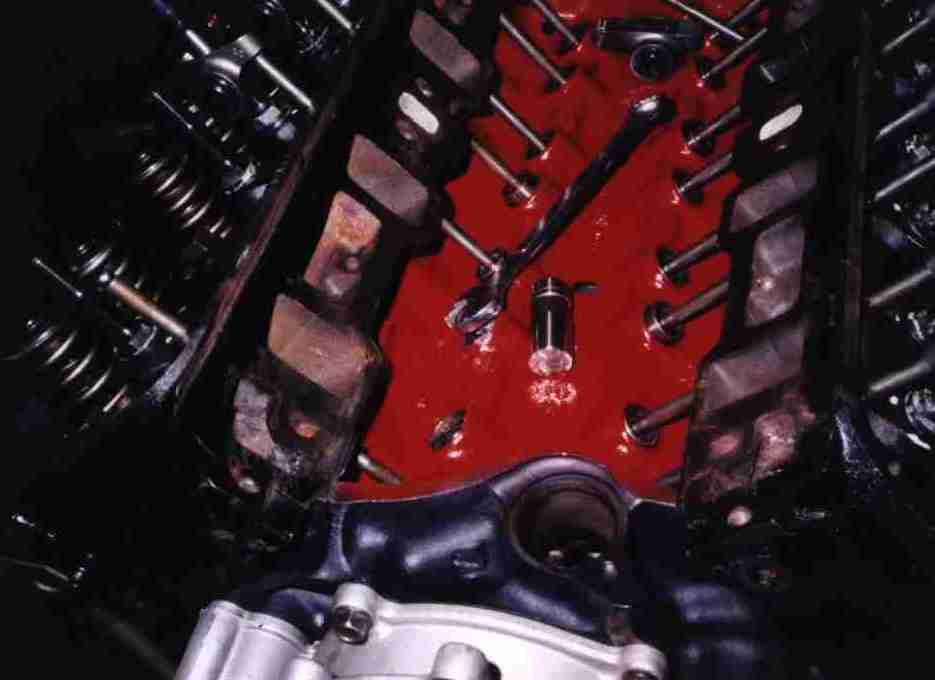

Crane titanium retainers, Competition Cams steel roller rockers, Sig Erson

300# springs from the cam kit, 7/16" studs, stud girdle, custom TFS hardened

pushrods. Rocker valleys have been sandblasted and coated with Tech Line "oil

shedding" stuff to help oil drain back faster. I don't know if it works, but

it's fancier than Rust-Oleum...

Crane titanium retainers, Competition Cams steel roller rockers, Sig Erson

300# springs from the cam kit, 7/16" studs, stud girdle, custom TFS hardened

pushrods. Rocker valleys have been sandblasted and coated with Tech Line "oil

shedding" stuff to help oil drain back faster. I don't know if it works, but

it's fancier than Rust-Oleum...

Plate bolts to valve cover holes, provides base for magnetic dial indicator.

Setting the hydraulic lifters to .030" preload.

Plate bolts to valve cover holes, provides base for magnetic dial indicator.

Setting the hydraulic lifters to .030" preload.

Accessories...

This is a pair of 5/16" steel plates for the new tri-Y headers. I've already

drilled, tapped, and countersunk and bolted two pieces together. The next

step is to bore the holes to size on the lathe.

This is a pair of 5/16" steel plates for the new tri-Y headers. I've already

drilled, tapped, and countersunk and bolted two pieces together. The next

step is to bore the holes to size on the lathe.

There are two of these plates, to attach the Ys to the collectors.

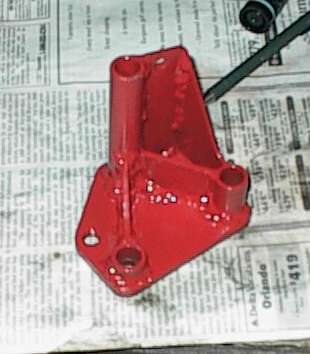

My fancy modified timing cover. I cut a hole to put an oil filler tube in

like an old 221 or 260.

My fancy modified timing cover. I cut a hole to put an oil filler tube in

like an old 221 or 260.

I needed some more radiator clearance, so I decided to go for it and changed to a short pump from a 2.5 liter Fiero. I used a chunk of 1/2" plate to mount it, then freehand-milled the proper reliefs in the back of the plate to direct water to the ports in the timing cover. I used a boring head to make the counterbore for the pump, drilled and tapped to mount it, etc. I took a lot of pictures, but they were on 35mm, and as happened more than once, the developers lost them.

With the short water pump grafted on, the next thing was to find a new lower

pulley. I found this one laying on the ground at a junkyard. I think it's

from an import. The diameter was correct to clear the sway bar, and the

sheaves were close in.

With the short water pump grafted on, the next thing was to find a new lower

pulley. I found this one laying on the ground at a junkyard. I think it's

from an import. The diameter was correct to clear the sway bar, and the

sheaves were close in.

I chucked the pulley in the lathe and bored out the center hole to match the

lip on the 302's damper.

I chucked the pulley in the lathe and bored out the center hole to match the

lip on the 302's damper.

Here's the pulley and the damper. They're a snug fit.

Here's the pulley and the damper. They're a snug fit.

With the damper and pulley together, I used a transfer punch to mark where the

new mounting holes had to be. A few passes with the drill and countersink,

and now I have a new lower pulley!

With the damper and pulley together, I used a transfer punch to mark where the

new mounting holes had to be. A few passes with the drill and countersink,

and now I have a new lower pulley!

The upper pulley is off a '77 Cadillac Eldorado. I had to shim it out 1/8" to

line up with the new lower pulley. The aluminum shim was made on the lathe

and drill press.

The upper pulley is off a '77 Cadillac Eldorado. I had to shim it out 1/8" to

line up with the new lower pulley. The aluminum shim was made on the lathe

and drill press.

With the pulleys done, I could do the air conditioning compressor. I went to

the junkyard and measured everything they had, and the ordinary GM R-4

compressor is the shortest of them all. It was designed to tuck into the

limited width of FWD engine compartments. First thing I did was to measure

the distance from the lower pulley groove to the front of the right cylinder

head, then weld a threaded bung onto a piece of steel to make a spacer

bracket.

With the pulleys done, I could do the air conditioning compressor. I went to

the junkyard and measured everything they had, and the ordinary GM R-4

compressor is the shortest of them all. It was designed to tuck into the

limited width of FWD engine compartments. First thing I did was to measure

the distance from the lower pulley groove to the front of the right cylinder

head, then weld a threaded bung onto a piece of steel to make a spacer

bracket.

With the spacer on, I could use a bolt to hold the compressor in place to

build the rest of the bracket. The compressor was rotated so the lines would

clear the headers. It's tucked in quite close to the water pump. You can see

the tube bolted to the accessory boss on the block above the pan rail; a tube

was welded to a threaded block that went on the back of the compressor, bolted

through from the front. I thought I took more pictures than this. [sigh]

There will be another bracket from one of the header bolts to an outboard

compressor bolt, to stabilize the compressor.

With the spacer on, I could use a bolt to hold the compressor in place to

build the rest of the bracket. The compressor was rotated so the lines would

clear the headers. It's tucked in quite close to the water pump. You can see

the tube bolted to the accessory boss on the block above the pan rail; a tube

was welded to a threaded block that went on the back of the compressor, bolted

through from the front. I thought I took more pictures than this. [sigh]

There will be another bracket from one of the header bolts to an outboard

compressor bolt, to stabilize the compressor.

A front shot. I welded up bits of tubing and flat stock to make the front

brackets; I'm just starting here.. Every bit helps. The compressor is

mounted solidly to the engine; a 1968 Torino V-belt idler pulley on the bottom

tensions the belt.

A front shot. I welded up bits of tubing and flat stock to make the front

brackets; I'm just starting here.. Every bit helps. The compressor is

mounted solidly to the engine; a 1968 Torino V-belt idler pulley on the bottom

tensions the belt.

That's the Mazda alternator in this shot; I decided on the GM alternator later.

You'll also notice the dipstick. The Milodon pan doesn't have provision for

the stock dipstick, as in a hole in the top baffle for it to go through. They

want you to use the screw-in dipstick in the T-sump. I drilled holes in the

pan baffles, then one in my crank scraper, and installed the stock dipstick.

Next I welded up the back bracket for the alternator. I chose a large frame

95 amp Delco SI unit; they're cheap, reliable, and easy to work with. Thick

flat stock bolts to the head, with the alternator pivot bolt hole offset past

the outside of the head so the alternator pivots correctly to tighten the belt

when swung. The other tubes and bits are for triangulation. The long tube

butts up against the back of the alternator.

Next I welded up the back bracket for the alternator. I chose a large frame

95 amp Delco SI unit; they're cheap, reliable, and easy to work with. Thick

flat stock bolts to the head, with the alternator pivot bolt hole offset past

the outside of the head so the alternator pivots correctly to tighten the belt

when swung. The other tubes and bits are for triangulation. The long tube

butts up against the back of the alternator.

Finished bracket, radiused, deburred, primed, and painted.

Finished bracket, radiused, deburred, primed, and painted.

Threaded hole on the side doesn't have any real purpose - there was metal

there, so I drilled and tapped it just in case I needed a place to mount a

torque strap or something.

...and mounted in place. The water pump inlet clears just fine. At the far

right corner of the T-sump is the screw-in plug Milodon wants you to use to

check the oil.

...and mounted in place. The water pump inlet clears just fine. At the far

right corner of the T-sump is the screw-in plug Milodon wants you to use to

check the oil.

Cardboard template for the front alternator bracket. It was very hard to

triangulate this part properly, so I went for thermonuclear overkill. This

bracket will form a cradle under the alternator, bolted to the water pump and

the cylinder head bracket I showed above.

Cardboard template for the front alternator bracket. It was very hard to

triangulate this part properly, so I went for thermonuclear overkill. This

bracket will form a cradle under the alternator, bolted to the water pump and

the cylinder head bracket I showed above.

I cut a pair of these out of .090" steel sheet.

I cut a pair of these out of .090" steel sheet.

Next, I cut more .090, then hammerformed it into curves to match the side

plates. I had to make separate pieces for the top and bottom.

Next, I cut more .090, then hammerformed it into curves to match the side

plates. I had to make separate pieces for the top and bottom.

Cradle with internal bracing welded in. I used square tubing instead of

"proper" triangulation. I figured there was enough metal there it wouldn't

really matter.

Cradle with internal bracing welded in. I used square tubing instead of

"proper" triangulation. I figured there was enough metal there it wouldn't

really matter.

Another shot of the cradle.

Another shot of the cradle.

Finished cradle. The alternator pivots between the ears. Weld on the water

pump side is unsightly, but what the heck.

Finished cradle. The alternator pivots between the ears. Weld on the water

pump side is unsightly, but what the heck.

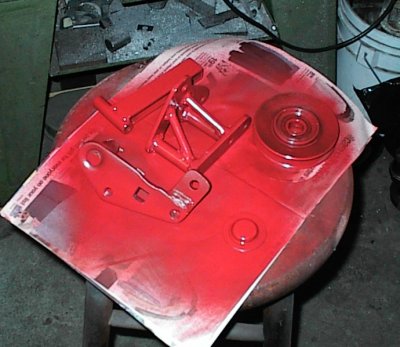

Painting all the fiddly bits. You can see the AC idler pulley and bracket

here.

Painting all the fiddly bits. You can see the AC idler pulley and bracket

here.

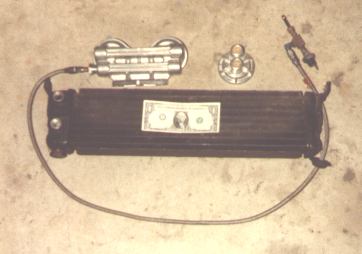

That's the original '79 RX-7 oil cooler. Huge, with internal regulator and

overpressure bypass. Compart its size to the dual filter block. Dollar bill

is for scale.

That's the original '79 RX-7 oil cooler. Huge, with internal regulator and

overpressure bypass. Compart its size to the dual filter block. Dollar bill

is for scale.